In the centre of Sukhum, the entire government is housed in an area the size of a football field.

Only as we approach Sukhum, the capital, do tiny shops appear, villas rise up in the hills and apartment blocks along the road suddenly show signs of life. We pass small train stations built in Stalin’s Empire style, where hordes of tourists may once have alighted right next to their hotel. Tunnels run under the road to the sea, where cafes and restaurants jut out into the water on piers. We are required to pick up our visas at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs as quickly as possible. In the centre of Sukhum, the entire government is housed in an area the size of a football field.

In the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, little more than a corridor in an office building, our names are carefully translated into Russian script. In the next room we pay and are given a green piece of paper worth $20. Meanwhile the minister, deputy ministers and officials talk loudly in the corridors. A small party seems to be taking place in the deputy minister’s office. Singing, shouting and laughter echo through the corridor. Two girls in high heels totter out of the room, staggering from the alcohol. A red-faced man drifts after them. “None of that, you come back! The party’s not over yet!” The girls are able to shake him off and flee out the door. “A birthday,” explains the young man who brings our visas.

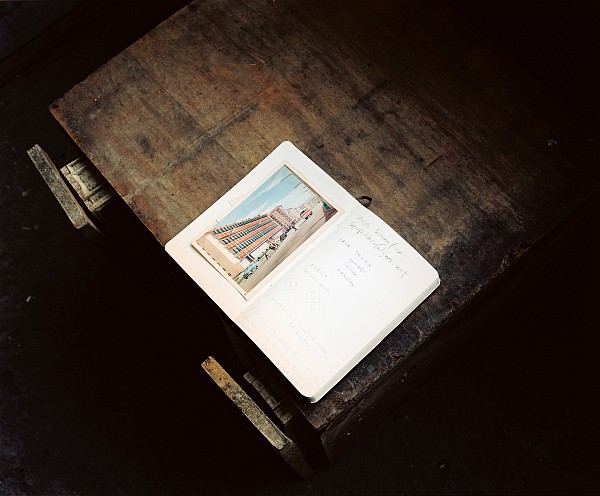

It is the everyday things that betray what it is like to live in a country that is recognised by only five other countries in the world. As a non-existent entity, Abkhazia has been without a postal service since 1991. Nevertheless, Eduard Konstantinovich Piliya, 72, is the director of the Abkhazian Post Office. He receives us in his large office in a monumental 19th-century building. He apologises that the tea lady has left, but grins broadly as he pulls a few glasses out of the cupboard. He screws the antenna off a mobile phone lying on his desk and fills our glasses with vodka. Cheers! Eduard is far beyond retirement age, but his job has been more or less improvised for the last 15 years. “I had more work before the war,” he admits frankly. “But I have since published more than 200 Abkhazian stamps!” He takes albums out of his wooden filing cabinet and leafs through them one by one. “These are true collector’s items.” He has stamps of animals, stamps of landscapes, stamps of Abkhazian heroes, even a stamp of John Lennon. He is proudest of the stamp that shows Abkhazia in the eighth century. “That’s when we were at our greatest,” he says. These days he is just muddling along. He and his staff continue to collect post, but people do not really send each other letters in Abkhazia. “They tend to visit each other instead,” he says. “The country isn’t very big.” Now, most of the collected letters and parcels are sent straight to Sochi. There the Russian postal service forwards them and hopes for the best. A few weeks later a postcard lands in our letterbox in The Netherlands. Of the large collection of Russian and Abkhazian stamps on it, curiously only the Abkhazian ones are franked. Piliya would be proud.

It is the everyday things that betray what it is like to live in a country that is recognised by only five other countries in the world. As a non-existent entity, Abkhazia has been without a postal service since 1991. Nevertheless, Eduard Konstantinovich Piliya, 72, is the director of the Abkhazian Post Office. He receives us in his large office in a monumental 19th-century building. He apologises that the tea lady has left, but grins broadly as he pulls a few glasses out of the cupboard. He screws the antenna off a mobile phone lying on his desk and fills our glasses with vodka. Cheers! Eduard is far beyond retirement age, but his job has been more or less improvised for the last 15 years. “I had more work before the war,” he admits frankly. “But I have since published more than 200 Abkhazian stamps!” He takes albums out of his wooden filing cabinet and leafs through them one by one. “These are true collector’s items.” He has stamps of animals, stamps of landscapes, stamps of Abkhazian heroes, even a stamp of John Lennon. He is proudest of the stamp that shows Abkhazia in the eighth century. “That’s when we were at our greatest,” he says. These days he is just muddling along. He and his staff continue to collect post, but people do not really send each other letters in Abkhazia. “They tend to visit each other instead,” he says. “The country isn’t very big.” Now, most of the collected letters and parcels are sent straight to Sochi. There the Russian postal service forwards them and hopes for the best. A few weeks later a postcard lands in our letterbox in The Netherlands. Of the large collection of Russian and Abkhazian stamps on it, curiously only the Abkhazian ones are franked. Piliya would be proud.

God’s favourite country

When God wanted to distribute the earth between its many peoples, he called them together. The English were given England, the Japanese Japan, the Russians Russia and so on. Only after the world had been divided up did the Abkhazians arrive. God and his angels looked surprised and dismayed. "We are sorry," said the Abkhazians. "We were on our way, but guests turned up and we had to serve them food and drink. Just as we were about to leave, more guests arrived."

“I now give you the most beautiful piece of land I know," said God.

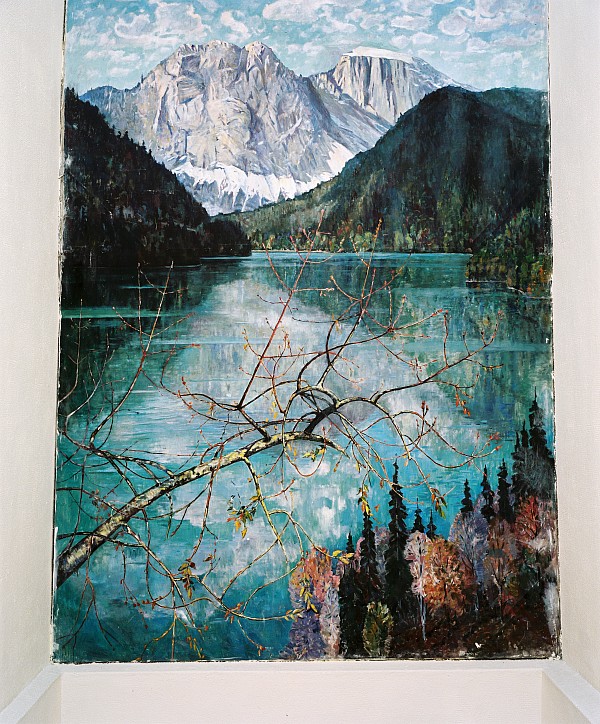

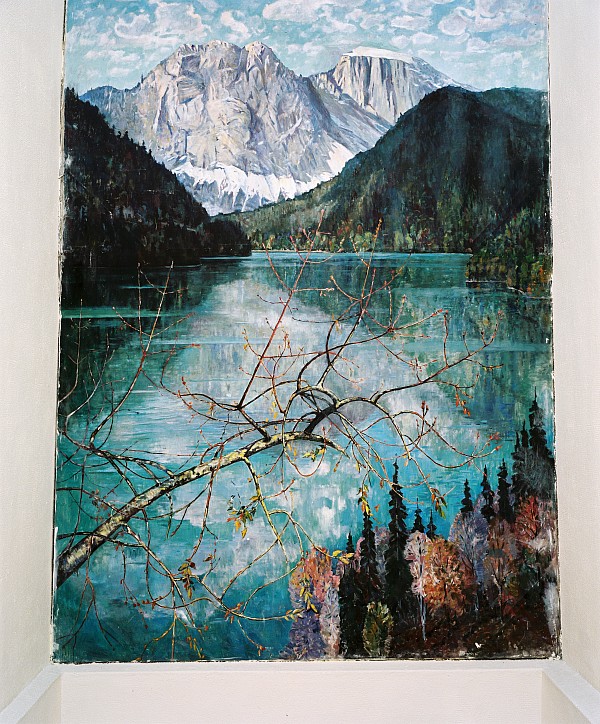

The promised land, as envisaged by the Ministry of Repatriation. Sukhum, Abkhazia, 2010

To punish the Abkhazians, God gave them the harshest piece of earth, cold, bare and dark. But the Abkhazians remained true to their culture. When one day, many years later, one of God's angels went to see what had become of them, he was welcomed with a sumptuous feast – as is customary for every guest. The angel reported this to God. Then God called the Abkhazians to him and rewarded their perseverance.

The promised land, as envisaged by the Ministry of Repatriation. Sukhum, Abkhazia, 2010

To punish the Abkhazians, God gave them the harshest piece of earth, cold, bare and dark. But the Abkhazians remained true to their culture. When one day, many years later, one of God's angels went to see what had become of them, he was welcomed with a sumptuous feast – as is customary for every guest. The angel reported this to God. Then God called the Abkhazians to him and rewarded their perseverance.

“I now give you the most beautiful piece of land I know," said God. “I was saving it from myself, but you are worth it. Remember though: like a beautiful young woman, your country will be coveted by everyone. It will be difficult to protect. If your descendants can't protect it, they will melt away like snow in the spring. If they can protect it, it will be theirs. Then it will be a truly beautiful country."

The Abkhazians tell themselves and their visitors this story to explain why they are who they are and why they have suffered so much conflict and bloodshed. More seasoned Caucuses travelers will find it hard to take this story seriously. It is likely that the dozens of peoples in these mountains tell a similar story to their visitors. That, at least, was our experience in Georgia and Chechnya.

Set amid pine trees on the coast, Pitsunda is one of Abkhazia’s main tourist draws. Pitsunda, Abkhazia, 2013.

Set amid pine trees on the coast, Pitsunda is one of Abkhazia’s main tourist draws. Pitsunda, Abkhazia, 2013.

Busstop designed by a young Zurab Tsereteli. Novi Afon, Abkhazia, 2013.

Busstop designed by a young Zurab Tsereteli. Novi Afon, Abkhazia, 2013.

The war

On 18 March 1989 – they perhaps foresaw the collapse of the Soviet Union – thousands of Abkhazians in Sukhum demanded independence for their autonomous republic, although still within the Soviet Union structure. At the beginning of April 1989, five months before the first protests in the East German city of Leipzig broke out – heralding the fall of the Berlin Wall and the end of Communism – hundreds of thousands of Georgians in Tbilisi demonstrated in turn against the Abkhazian claims and for Georgian independence outside the Soviet Union. The Georgians got ahead of themselves. The demonstration was crushed, with dozens dead and thousands wounded as a result.

Opposing the separatist regime in Abkhazia, led by the historian Vladislav Ardzinba, was the almost revolutionary regime of the Soviet dissident and poet Zviad Gamsakhurdia. The latter had, in response to Russian attempts to Russify Georgia since 1955, become a Georgian nationalist. In his rhetoric, Georgia was, as a religious national state, superior to the small federal states and minorities such as the Ossetians, Ajarians, Armenians and Abkhazians. In the first democratic elections Gamsakhurdia won with 64 per cent of the vote..

Zviad Gamsakhurdia

Georgia for Georgians, he proclaimed.

Georgia for Georgians, he proclaimed, thereby setting in motion a series of events that gained speed as they hurtled towards horrific inter-ethnic violence. Under his short leadership, Georgia became embroiled in civil war, in which countless rival militias conspired with each other to take over the government and the country. Through a troika of anti-Gamsakhurdia militias, Eduard Shevardnadze was brought in from Moscow where, since 1985, he had been the face of the perestroika abroad.

The war in Abkhazia played out against the complete governmental and social disintegration of the Soviet Union.

Prior to that, he had spent nearly three decades in the highest echelons of the Communist Party in Georgia. In that capacity he had already arrested the dissident Gamsakhurdia and sent him to a labour camp in Dagestan. However, Shevardnadze did not seek peace with the separatists in Abkhazia either. The conflict derailed. The war in Abkhazia played out against the complete governmental and social disintegration of the Soviet Union. The economy was floundering, the army was stretched thin across the newly created countries and sitting leaders and dissidents fought for power in new state systems. Geopolitical relations in a world after the collapse of the Soviet Union, without the self-evident leadership role of Moscow, had yet to crystallise.

Around the central train station in Sukhum, all seems to be broken. Sukhum, Abkhazia, 2007.

Around the central train station in Sukhum, all seems to be broken. Sukhum, Abkhazia, 2007.

A gruesome struggle

Besides the Georgian army, several militias with their own agendas were also active in Georgia and Abkhazia, all responsible for the most grievous violation of human rights. The war in Abkhazia against the Georgians was fought by an unlikely coalition. Islamic fighters from Chechnya, Cossacks from South Russia, troops and agents from the Kremlin, the Abkhazian diaspora and volunteers fought side by side with the Abkhazians. Russian aeroplanes bombed Georgian positions, in response to which Georgians carried out reprisals with weapons obtained via Russia. The Moloch Soviet Union may have disappeared overnight, but contacts were still maintained with civil servants, Kremlin officials, army officers, inspectors at munitions depots and KGB staff. In the informal circuit – and in those chaotic days of the former Soviet Union, what wasn’t informal? – anything could be arranged. In reports from that period, a cycle of increasingly horrific crimes becomes apparent. In this dirty war men like Basayev – the future Chechen guerrilla leader behind the Beslan school and Moscow Nord-Ost theatre hostage crises, among others – learned their grim handiwork. In its brutality, the war in Abkhazia is comparable to Bosnia. Here too brothers and neighbours attacked each other; here too a market was bombed, killing dozens. But here there was no international UN force which eventually intervened. This was a nothing-to-do-with-me show, collateral damage that was part and parcel of the fall of the Cold War enemy.

It was worth it

Sanatorium 'Georgia' in the hill with a view on the sea. Gagra, Abkhazia, 2013.

Located in the west of the country near the Russian border, Gagra is the pearl of Abkhazia. The surroundings are spectacular, nestled in a sort of basin of the Black Sea, with lush green hills that rise steeply to meet the Caucasus Mountains. Gagra was spared the war, and many of its older monumental sanatoria and restaurants are still intact. One of these sanatoria now houses the war invalids’ rehabilitation centre. We speak to Tina, Viacheslav and Leonid, who are 57, 60 and 68 respectively. The men both wear acrylic Adidas tracksuits. When we ask about them, they joke that their wives were shopping together at the market and both liked the same tracksuit. “I studied in Georgia,” says Leonid, the eldest of the three. “When I was young I couldn’t even speak Abkhazian. Subsequently, and with great difficulty, I taught it to my myself.” He was a teacher and head of the school in Gudauta. His Georgian students called him Joseph because they thought he looked like Stalin. Many of them later fought against him on the front. Twenty-eight of his students died. He starts to cry softly as he talks about it. Tina puts her arm around his shoulders. “War isn’t good,” she says, “neither for the winner, nor the loser. Peace would have been better, but everyone who took part in the war on our side would say that it was worth the pain and suffering. For the motherland.”

Sanatorium 'Georgia' in the hill with a view on the sea. Gagra, Abkhazia, 2013.

Located in the west of the country near the Russian border, Gagra is the pearl of Abkhazia. The surroundings are spectacular, nestled in a sort of basin of the Black Sea, with lush green hills that rise steeply to meet the Caucasus Mountains. Gagra was spared the war, and many of its older monumental sanatoria and restaurants are still intact. One of these sanatoria now houses the war invalids’ rehabilitation centre. We speak to Tina, Viacheslav and Leonid, who are 57, 60 and 68 respectively. The men both wear acrylic Adidas tracksuits. When we ask about them, they joke that their wives were shopping together at the market and both liked the same tracksuit. “I studied in Georgia,” says Leonid, the eldest of the three. “When I was young I couldn’t even speak Abkhazian. Subsequently, and with great difficulty, I taught it to my myself.” He was a teacher and head of the school in Gudauta. His Georgian students called him Joseph because they thought he looked like Stalin. Many of them later fought against him on the front. Twenty-eight of his students died. He starts to cry softly as he talks about it. Tina puts her arm around his shoulders. “War isn’t good,” she says, “neither for the winner, nor the loser. Peace would have been better, but everyone who took part in the war on our side would say that it was worth the pain and suffering. For the motherland.”

Tina. Gagra, Abkhazia, 2010.

Tina. Gagra, Abkhazia, 2010.

Tina

It was worth the pain and suffering. For the motherland.

Viacheslav and Leonid. Gagra, Abkhazia, 2010.

Viacheslav and Leonid. Gagra, Abkhazia, 2010.

Tina tells us that she is a Russian, from Krasnodar. As a nurse, she felt compelled to help the Abkhazians in their losing battle. “A Georgian general said that they’d destroy Abkhazia in 25 minutes. Then volunteers arrived. They came from all over the world, I even saw black people.” On the Gumista front, just north of Sukhum, she was wounded in her stomach and ribs. Her stomach still gives her a lot of trouble. She is severely disabled. “War’s war, that’s the way it goes,” she says. “I’ve made my peace with it.”

Abkhazia faced difficult years ahead in complete isolation.

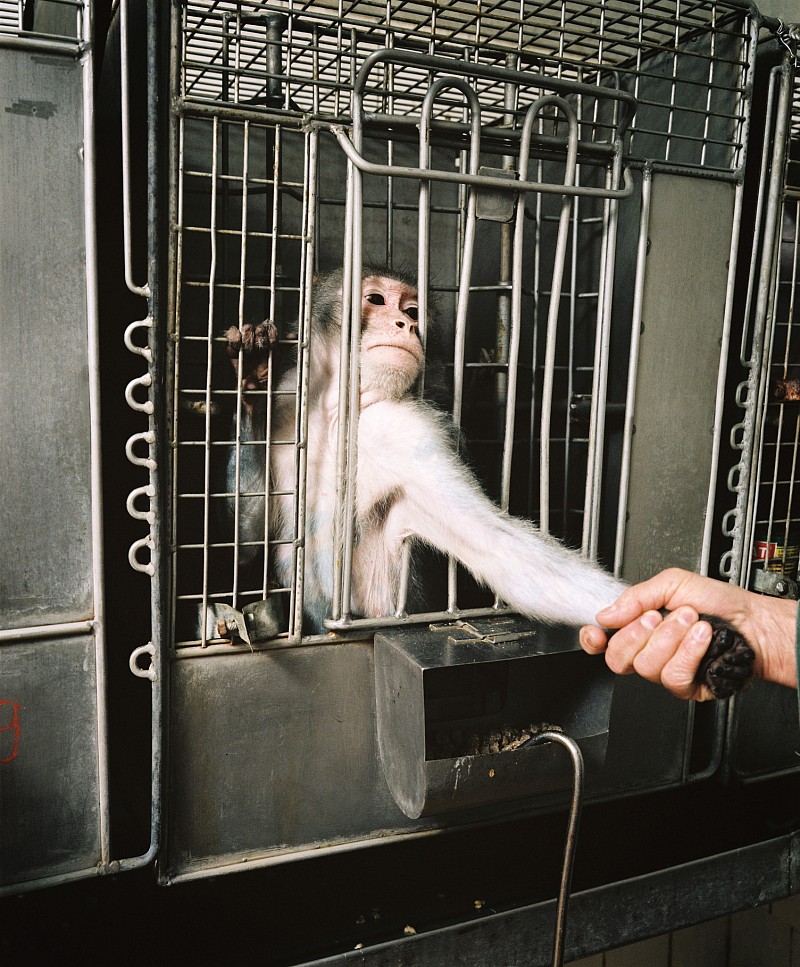

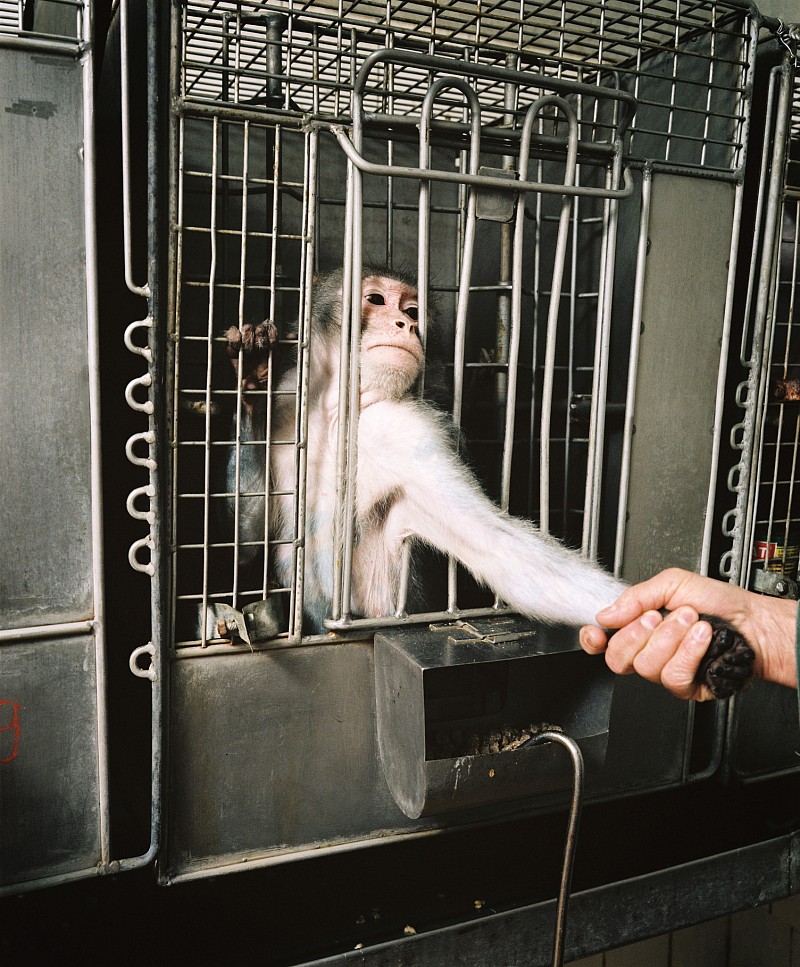

In de heuvels boven de hoofdstad Soechoem ligt het apenlaboratorium. Het is voor toeristen misschien wel het meest populaire uitje in Abchazie. Een vrolijke plek is het niet. Wie aankomt wordt ontvangen door een klein leger apen, dat zielig naast elkaar in een bevuilde kooi zit, voorzichtig plukkend aan elkaar. Sommigen zitten bibberend op een stok elders. Daarachter bevinden zich de gebouwen van het onderzoeksinstituut. Dames in witte zusterpakken lopen met troggen, dweilen en bezems door de groene straatjes. Her en der steken kooien uit de gebouwen, waar soms weifelend een aapje om de hoek kijkt. Vladimir Spironovich is een van de onderzoekers aan het wetenschappelijke instituut. Meteen maakt hij gehakt van het grote verhaal dat rondgaat: dat hier in Sovjet-Unie een leger apen werd gekruisd met mensen, om zo een vechtmens te kweken, een wezen met de intelligentie van de mens, en de brute kracht en handigheid van de aap. Het spreekt tot de verbeelding, dat geeft zelfs Spironovich toe. Maar hij kan het niet genoeg benadrukken: Het. Is. Onzin. ‘Wat wel wel hebben gedaan,’ zegt hij trots, ‘is belangrijke doorbraken in het wereldwijde kankeronderzoek helpen bevestigen.’ Ergens achter een van de gebouwen bevindt zich een houten, verrotte en volledig kapotte stellage. Dit is een historische plek. In deze installatie werden de apen uit het laboratorium lang door elkaar geschud en onderworpen aan g-krachten zodat ze zich konden voorbereiden op een ruimtereis. ‘Acht apen hebben we de ruimte ingestuurd,’ zegt Spiridonovich trots. Het apeninstituut bereidt zich nu voor op een nieuwe taak. Met Russische ruimtevaarttuigen moeten de eerste apen ooit naar Mars worden gestuurd. ‘Mensen kunnen de straling onderweg nog niet aan,’ zegt Spiridonovich. Vol medelijden laten we de apen achter ons.In de heuvels boven de hoofdstad Soechoem ligt het apenlaboratorium. Het is voor toeristen misschien wel het meest populaire uitje in Abchazie. Een vrolijke plek is het niet. Wie aankomt wordt ontvangen door een klein leger apen, dat zielig naast elkaar in een bevuilde kooi zit, voorzichtig plukkend aan elkaar. Sommigen zitten bibberend op een stok elders. Daarachter bevinden zich de gebouwen van het onderzoeksinstituut. Dames in witte zusterpakken lopen met troggen, dweilen en bezems door de groene straatjes. Her en der steken kooien uit de gebouwen, waar soms weifelend een aapje om de hoek kijkt. Vladimir Spironovich is een van de onderzoekers aan het wetenschappelijke instituut. Meteen maakt hij gehakt van het grote verhaal dat rondgaat: dat hier in Sovjet-Unie een leger apen werd gekruisd met mensen, om zo een vechtmens te kweken, een wezen met de intelligentie van de mens, en de brute kracht en handigheid van de aap. Het spreekt tot de verbeelding, dat geeft zelfs Spironovich toe. Maar hij kan het niet genoeg benadrukken: Het. Is. Onzin. ‘Wat wel wel hebben gedaan,’ zegt hij trots, ‘is belangrijke doorbraken in het wereldwijde kankeronderzoek helpen bevestigen.’ Ergens achter een van de gebouwen bevindt zich een houten, verrotte en volledig kapotte stellage. Dit is een historische plek. In deze installatie werden de apen uit het laboratorium lang door elkaar geschud en onderworpen aan g-krachten zodat ze zich konden voorbereiden op een ruimtereis. ‘Acht apen hebben we de ruimte ingestuurd,’ zegt Spiridonovich trots. Het apeninstituut bereidt zich nu voor op een nieuwe taak. Met Russische ruimtevaarttuigen moeten de eerste apen ooit naar Mars worden gestuurd. ‘Mensen kunnen de straling onderweg nog niet aan,’ zegt Spiridonovich. Vol medelijden laten we de apen achter ons.In de heuvels boven de hoofdstad Soechoem ligt het apenlaboratorium. Het is voor toeristen misschien wel het meest populaire uitje in Abchazie. Een vrolijke plek is het niet. Wie aankomt wordt ontvangen door een klein leger apen, dat zielig naast elkaar in een bevuilde kooi zit, voorzichtig plukkend aan elkaar. Sommigen zitten bibberend op een stok elders. Daarachter bevinden zich de gebouwen van het onderzoeksinstituut. Dames in witte zusterpakken lopen met troggen, dweilen en bezems door de groene straatjes. Her en der steken kooien uit de gebouwen, waar soms weifelend een aapje om de hoek kijkt. Vladimir Spironovich is een van de onderzoekers aan het wetenschappelijke instituut. Meteen maakt hij gehakt van het grote verhaal dat rondgaat: dat hier in Sovjet-Unie een leger apen werd gekruisd met mensen, om zo een vechtmens te kweken, een wezen met de intelligentie van de mens, en de brute kracht en handigheid van de aap. Het spreekt tot de verbeelding, dat geeft zelfs Spironovich toe. Maar hij kan het niet genoeg benadrukken: Het. Is. Onzin. ‘Wat wel wel hebben gedaan,’ zegt hij trots, ‘is belangrijke doorbraken in het wereldwijde kankeronderzoek helpen bevestigen.’ Ergens achter een van de gebouwen bevindt zich een houten, verrotte en volledig kapotte stellage. Dit is een historische plek. In deze installatie werden de apen uit het laboratorium lang door elkaar geschud en onderworpen aan g-krachten zodat ze zich konden voorbereiden op een ruimtereis. ‘Acht apen hebben we de ruimte ingestuurd,’ zegt Spiridonovich trots. Het apeninstituut bereidt zich nu voor op een nieuwe taak. Met Russische ruimtevaarttuigen moeten de eerste apen ooit naar Mars worden gestuurd. ‘Mensen kunnen de straling onderweg nog niet aan,’ zegt Spiridonovich. Vol medelijden laten we de apen achter ons.In de heuvels boven de hoofdstad Soechoem ligt het apenlaboratorium. Het is voor toeristen misschien wel het meest populaire uitje in Abchazie. Een vrolijke plek is het niet. Wie aankomt wordt ontvangen door een klein leger apen, dat zielig naast elkaar in een bevuilde kooi zit, voorzichtig plukkend aan elkaar. Sommigen zitten bibberend op een stok elders. Daarachter bevinden zich de gebouwen van het onderzoeksinstituut. Dames in witte zusterpakken lopen met troggen, dweilen en bezems door de groene straatjes. Her en der steken kooien uit de gebouwen, waar soms weifelend een aapje om de hoek kijkt. Vladimir Spironovich is een van de onderzoekers aan het wetenschappelijke instituut. Meteen maakt hij gehakt van het grote verhaal dat rondgaat: dat hier in Sovjet-Unie een leger apen werd gekruisd met mensen, om zo een vechtmens te kweken, een wezen met de intelligentie van de mens, en de brute kracht en handigheid van de aap. Het spreekt tot de verbeelding, dat geeft zelfs Spironovich toe. Maar hij kan het niet genoeg benadrukken: Het. Is. Onzin. ‘Wat wel wel hebben gedaan,’ zegt hij trots, ‘is belangrijke doorbraken in het wereldwijde kankeronderzoek helpen bevestigen.’ Ergens achter een van de gebouwen bevindt zich een houten, verrotte en volledig kapotte stellage. Dit is een historische plek. In deze installatie werden de apen uit het laboratorium lang door elkaar geschud en onderworpen aan g-krachten zodat ze zich konden voorbereiden op een ruimtereis. ‘Acht apen hebben we de ruimte ingestuurd,’ zegt Spiridonovich trots. Het apeninstituut bereidt zich nu voor op een nieuwe taak. Met Russische ruimtevaarttuigen moeten de eerste apen ooit naar Mars worden gestuurd. ‘Mensen kunnen de straling onderweg nog niet aan,’ zegt Spiridonovich. Vol medelijden laten we de apen achter ons.In de heuvels boven de hoofdstad Soechoem ligt het apenlaboratorium. Het is voor toeristen misschien wel het meest populaire uitje in Abchazie. Een vrolijke plek is het niet. Wie aankomt wordt ontvangen door een klein leger apen, dat zielig naast elkaar in een bevuilde kooi zit, voorzichtig plukkend aan elkaar. Sommigen zitten bibberend op een stok elders. Daarachter bevinden zich de gebouwen van het onderzoeksinstituut. Dames in witte zusterpakken lopen met troggen, dweilen en bezems door de groene straatjes. Her en der steken kooien uit de gebouwen, waar soms weifelend een aapje om de hoek kijkt. Vladimir Spironovich is een van de onderzoekers aan het wetenschappelijke instituut. Meteen maakt hij gehakt van het grote verhaal dat rondgaat: dat hier in Sovjet-Unie een leger apen werd gekruisd met mensen, om zo een vechtmens te kweken, een wezen met de intelligentie van de mens, en de brute kracht en handigheid van de aap. Het spreekt tot de verbeelding, dat geeft zelfs Spironovich toe. Maar hij kan het niet genoeg benadrukken: Het. Is. Onzin. ‘Wat wel wel hebben gedaan,’ zegt hij trots, ‘is belangrijke doorbraken in het wereldwijde kankeronderzoek helpen bevestigen.’ Ergens achter een van de gebouwen bevindt zich een houten, verrotte en volledig kapotte stellage. Dit is een historische plek. In deze installatie werden de apen uit het laboratorium lang door elkaar geschud en onderworpen aan g-krachten zodat ze zich konden voorbereiden op een ruimtereis. ‘Acht apen hebben we de ruimte ingestuurd,’ zegt Spiridonovich trots. Het apeninstituut bereidt zich nu voor op een nieuwe taak. Met Russische ruimtevaarttuigen moeten de eerste apen ooit naar Mars worden gestuurd. ‘Mensen kunnen de straling onderweg nog niet aan,’ zegt Spiridonovich. Vol medelijden laten we de apen achter ons.In de heuvels boven de hoofdstad Soechoem ligt het apenlaboratorium. Het is voor toeristen misschien wel het meest populaire uitje in Abchazie. Een vrolijke plek is het niet. Wie aankomt wordt ontvangen door een klein leger apen, dat zielig naast elkaar in een bevuilde kooi zit, voorzichtig plukkend aan elkaar. Sommigen zitten bibberend op een stok elders. Daarachter bevinden zich de gebouwen van het onderzoeksinstituut. Dames in witte zusterpakken lopen met troggen, dweilen en bezems door de groene straatjes. Her en der steken kooien uit de gebouwen, waar soms weifelend een aapje om de hoek kijkt. Vladimir Spironovich is een van de onderzoekers aan het wetenschappelijke instituut. Meteen maakt hij gehakt van het grote verhaal dat rondgaat: dat hier in Sovjet-Unie een leger apen werd gekruisd met mensen, om zo een vechtmens te kweken, een wezen met de intelligentie van de mens, en de brute kracht en handigheid van de aap. Het spreekt tot de verbeelding, dat geeft zelfs Spironovich toe. Maar hij kan het niet genoeg benadrukken: Het. Is. Onzin. ‘Wat wel wel hebben gedaan,’ zegt hij trots, ‘is belangrijke doorbraken in het wereldwijde kankeronderzoek helpen bevestigen.’ Ergens achter een van de gebouwen bevindt zich een houten, verrotte en volledig kapotte stellage. Dit is een historische plek. In deze installatie werden de apen uit het laboratorium lang door elkaar geschud en onderworpen aan g-krachten zodat ze zich konden voorbereiden op een ruimtereis. ‘Acht apen hebben we de ruimte ingestuurd,’ zegt Spiridonovich trots. Het apeninstituut bereidt zich nu voor op een nieuwe taak. Met Russische ruimtevaarttuigen moeten de eerste apen ooit naar Mars worden gestuurd. ‘Mensen kunnen de straling onderweg nog niet aan,’ zegt Spiridonovich. Vol medelijden laten we de apen achter ons.

In the hills above Sukhum is a monkey laboratory, possibly the most popular tourist attraction in Abkhazia. It is a depressing place. Visitors are received by a small army of monkeys, who sit huddled in a dirty cage, carefully grooming one another. Others sit shivering on poles in separate enclosures. The buildings of the research institute loom in the background. Women in white nurses’ uniforms carry troughs, mops and brooms through the green streets. Cages protrude here and there from the buildings, and an occasional monkey hesitantly peers out at passers-by. Vladimir Spironovich is one of the researchers at the institute. He immediately discredits a story that has been circulating: in the Soviet era, monkeys were crossbred with people to create a super species with the intelligence of humans and the brute strength and dexterity of monkeys. It is a fantastical story, Spironovich admits, but he cannot emphasise enough: It. Is. Nonsense. “What we have done,” he says proudly, “is help confirm important breakthroughs in global cancer research.” Somewhere behind one of the buildings is a rotting wooden platform. This is a historical site. In this installation, monkeys from the laboratory were subjected to extensive shaking and g-forces to prepare them for space travel. “We sent eight monkeys into space,” Spironovich says with pride. The institute is now reaching for a new frontier: using a Russian spacecraft to put the first monkey on Mars. “Humans can’t yet handle the radiation on the journey,” he says. Filled with compassion, we leave the monkeys behind us.

In de heuvels boven de hoofdstad Soechoem ligt het apenlaboratorium. Het is voor toeristen misschien wel het meest populaire uitje in Abchazie. Een vrolijke plek is het niet. Wie aankomt wordt ontvangen door een klein leger apen, dat zielig naast elkaar in een bevuilde kooi zit, voorzichtig plukkend aan elkaar. Sommigen zitten bibberend op een stok elders. Daarachter bevinden zich de gebouwen van het onderzoeksinstituut. Dames in witte zusterpakken lopen met troggen, dweilen en bezems door de groene straatjes. Her en der steken kooien uit de gebouwen, waar soms weifelend een aapje om de hoek kijkt. Vladimir Spironovich is een van de onderzoekers aan het wetenschappelijke instituut. Meteen maakt hij gehakt van het grote verhaal dat rondgaat: dat hier in Sovjet-Unie een leger apen werd gekruisd met mensen, om zo een vechtmens te kweken, een wezen met de intelligentie van de mens, en de brute kracht en handigheid van de aap. Het spreekt tot de verbeelding, dat geeft zelfs Spironovich toe. Maar hij kan het niet genoeg benadrukken: Het. Is. Onzin. ‘Wat wel wel hebben gedaan,’ zegt hij trots, ‘is belangrijke doorbraken in het wereldwijde kankeronderzoek helpen bevestigen.’ Ergens achter een van de gebouwen bevindt zich een houten, verrotte en volledig kapotte stellage. Dit is een historische plek. In deze installatie werden de apen uit het laboratorium lang door elkaar geschud en onderworpen aan g-krachten zodat ze zich konden voorbereiden op een ruimtereis. ‘Acht apen hebben we de ruimte ingestuurd,’ zegt Spiridonovich trots. Het apeninstituut bereidt zich nu voor op een nieuwe taak. Met Russische ruimtevaarttuigen moeten de eerste apen ooit naar Mars worden gestuurd. ‘Mensen kunnen de straling onderweg nog niet aan,’ zegt Spiridonovich. Vol medelijden laten we de apen achter ons.In de heuvels boven de hoofdstad Soechoem ligt het apenlaboratorium. Het is voor toeristen misschien wel het meest populaire uitje in Abchazie. Een vrolijke plek is het niet. Wie aankomt wordt ontvangen door een klein leger apen, dat zielig naast elkaar in een bevuilde kooi zit, voorzichtig plukkend aan elkaar. Sommigen zitten bibberend op een stok elders. Daarachter bevinden zich de gebouwen van het onderzoeksinstituut. Dames in witte zusterpakken lopen met troggen, dweilen en bezems door de groene straatjes. Her en der steken kooien uit de gebouwen, waar soms weifelend een aapje om de hoek kijkt. Vladimir Spironovich is een van de onderzoekers aan het wetenschappelijke instituut. Meteen maakt hij gehakt van het grote verhaal dat rondgaat: dat hier in Sovjet-Unie een leger apen werd gekruisd met mensen, om zo een vechtmens te kweken, een wezen met de intelligentie van de mens, en de brute kracht en handigheid van de aap. Het spreekt tot de verbeelding, dat geeft zelfs Spironovich toe. Maar hij kan het niet genoeg benadrukken: Het. Is. Onzin. ‘Wat wel wel hebben gedaan,’ zegt hij trots, ‘is belangrijke doorbraken in het wereldwijde kankeronderzoek helpen bevestigen.’ Ergens achter een van de gebouwen bevindt zich een houten, verrotte en volledig kapotte stellage. Dit is een historische plek. In deze installatie werden de apen uit het laboratorium lang door elkaar geschud en onderworpen aan g-krachten zodat ze zich konden voorbereiden op een ruimtereis. ‘Acht apen hebben we de ruimte ingestuurd,’ zegt Spiridonovich trots. Het apeninstituut bereidt zich nu voor op een nieuwe taak. Met Russische ruimtevaarttuigen moeten de eerste apen ooit naar Mars worden gestuurd. ‘Mensen kunnen de straling onderweg nog niet aan,’ zegt Spiridonovich. Vol medelijden laten we de apen achter ons.In de heuvels boven de hoofdstad Soechoem ligt het apenlaboratorium. Het is voor toeristen misschien wel het meest populaire uitje in Abchazie. Een vrolijke plek is het niet. Wie aankomt wordt ontvangen door een klein leger apen, dat zielig naast elkaar in een bevuilde kooi zit, voorzichtig plukkend aan elkaar. Sommigen zitten bibberend op een stok elders. Daarachter bevinden zich de gebouwen van het onderzoeksinstituut. Dames in witte zusterpakken lopen met troggen, dweilen en bezems door de groene straatjes. Her en der steken kooien uit de gebouwen, waar soms weifelend een aapje om de hoek kijkt. Vladimir Spironovich is een van de onderzoekers aan het wetenschappelijke instituut. Meteen maakt hij gehakt van het grote verhaal dat rondgaat: dat hier in Sovjet-Unie een leger apen werd gekruisd met mensen, om zo een vechtmens te kweken, een wezen met de intelligentie van de mens, en de brute kracht en handigheid van de aap. Het spreekt tot de verbeelding, dat geeft zelfs Spironovich toe. Maar hij kan het niet genoeg benadrukken: Het. Is. Onzin. ‘Wat wel wel hebben gedaan,’ zegt hij trots, ‘is belangrijke doorbraken in het wereldwijde kankeronderzoek helpen bevestigen.’ Ergens achter een van de gebouwen bevindt zich een houten, verrotte en volledig kapotte stellage. Dit is een historische plek. In deze installatie werden de apen uit het laboratorium lang door elkaar geschud en onderworpen aan g-krachten zodat ze zich konden voorbereiden op een ruimtereis. ‘Acht apen hebben we de ruimte ingestuurd,’ zegt Spiridonovich trots. Het apeninstituut bereidt zich nu voor op een nieuwe taak. Met Russische ruimtevaarttuigen moeten de eerste apen ooit naar Mars worden gestuurd. ‘Mensen kunnen de straling onderweg nog niet aan,’ zegt Spiridonovich. Vol medelijden laten we de apen achter ons.In de heuvels boven de hoofdstad Soechoem ligt het apenlaboratorium. Het is voor toeristen misschien wel het meest populaire uitje in Abchazie. Een vrolijke plek is het niet. Wie aankomt wordt ontvangen door een klein leger apen, dat zielig naast elkaar in een bevuilde kooi zit, voorzichtig plukkend aan elkaar. Sommigen zitten bibberend op een stok elders. Daarachter bevinden zich de gebouwen van het onderzoeksinstituut. Dames in witte zusterpakken lopen met troggen, dweilen en bezems door de groene straatjes. Her en der steken kooien uit de gebouwen, waar soms weifelend een aapje om de hoek kijkt. Vladimir Spironovich is een van de onderzoekers aan het wetenschappelijke instituut. Meteen maakt hij gehakt van het grote verhaal dat rondgaat: dat hier in Sovjet-Unie een leger apen werd gekruisd met mensen, om zo een vechtmens te kweken, een wezen met de intelligentie van de mens, en de brute kracht en handigheid van de aap. Het spreekt tot de verbeelding, dat geeft zelfs Spironovich toe. Maar hij kan het niet genoeg benadrukken: Het. Is. Onzin. ‘Wat wel wel hebben gedaan,’ zegt hij trots, ‘is belangrijke doorbraken in het wereldwijde kankeronderzoek helpen bevestigen.’ Ergens achter een van de gebouwen bevindt zich een houten, verrotte en volledig kapotte stellage. Dit is een historische plek. In deze installatie werden de apen uit het laboratorium lang door elkaar geschud en onderworpen aan g-krachten zodat ze zich konden voorbereiden op een ruimtereis. ‘Acht apen hebben we de ruimte ingestuurd,’ zegt Spiridonovich trots. Het apeninstituut bereidt zich nu voor op een nieuwe taak. Met Russische ruimtevaarttuigen moeten de eerste apen ooit naar Mars worden gestuurd. ‘Mensen kunnen de straling onderweg nog niet aan,’ zegt Spiridonovich. Vol medelijden laten we de apen achter ons.In de heuvels boven de hoofdstad Soechoem ligt het apenlaboratorium. Het is voor toeristen misschien wel het meest populaire uitje in Abchazie. Een vrolijke plek is het niet. Wie aankomt wordt ontvangen door een klein leger apen, dat zielig naast elkaar in een bevuilde kooi zit, voorzichtig plukkend aan elkaar. Sommigen zitten bibberend op een stok elders. Daarachter bevinden zich de gebouwen van het onderzoeksinstituut. Dames in witte zusterpakken lopen met troggen, dweilen en bezems door de groene straatjes. Her en der steken kooien uit de gebouwen, waar soms weifelend een aapje om de hoek kijkt. Vladimir Spironovich is een van de onderzoekers aan het wetenschappelijke instituut. Meteen maakt hij gehakt van het grote verhaal dat rondgaat: dat hier in Sovjet-Unie een leger apen werd gekruisd met mensen, om zo een vechtmens te kweken, een wezen met de intelligentie van de mens, en de brute kracht en handigheid van de aap. Het spreekt tot de verbeelding, dat geeft zelfs Spironovich toe. Maar hij kan het niet genoeg benadrukken: Het. Is. Onzin. ‘Wat wel wel hebben gedaan,’ zegt hij trots, ‘is belangrijke doorbraken in het wereldwijde kankeronderzoek helpen bevestigen.’ Ergens achter een van de gebouwen bevindt zich een houten, verrotte en volledig kapotte stellage. Dit is een historische plek. In deze installatie werden de apen uit het laboratorium lang door elkaar geschud en onderworpen aan g-krachten zodat ze zich konden voorbereiden op een ruimtereis. ‘Acht apen hebben we de ruimte ingestuurd,’ zegt Spiridonovich trots. Het apeninstituut bereidt zich nu voor op een nieuwe taak. Met Russische ruimtevaarttuigen moeten de eerste apen ooit naar Mars worden gestuurd. ‘Mensen kunnen de straling onderweg nog niet aan,’ zegt Spiridonovich. Vol medelijden laten we de apen achter ons.In de heuvels boven de hoofdstad Soechoem ligt het apenlaboratorium. Het is voor toeristen misschien wel het meest populaire uitje in Abchazie. Een vrolijke plek is het niet. Wie aankomt wordt ontvangen door een klein leger apen, dat zielig naast elkaar in een bevuilde kooi zit, voorzichtig plukkend aan elkaar. Sommigen zitten bibberend op een stok elders. Daarachter bevinden zich de gebouwen van het onderzoeksinstituut. Dames in witte zusterpakken lopen met troggen, dweilen en bezems door de groene straatjes. Her en der steken kooien uit de gebouwen, waar soms weifelend een aapje om de hoek kijkt. Vladimir Spironovich is een van de onderzoekers aan het wetenschappelijke instituut. Meteen maakt hij gehakt van het grote verhaal dat rondgaat: dat hier in Sovjet-Unie een leger apen werd gekruisd met mensen, om zo een vechtmens te kweken, een wezen met de intelligentie van de mens, en de brute kracht en handigheid van de aap. Het spreekt tot de verbeelding, dat geeft zelfs Spironovich toe. Maar hij kan het niet genoeg benadrukken: Het. Is. Onzin. ‘Wat wel wel hebben gedaan,’ zegt hij trots, ‘is belangrijke doorbraken in het wereldwijde kankeronderzoek helpen bevestigen.’ Ergens achter een van de gebouwen bevindt zich een houten, verrotte en volledig kapotte stellage. Dit is een historische plek. In deze installatie werden de apen uit het laboratorium lang door elkaar geschud en onderworpen aan g-krachten zodat ze zich konden voorbereiden op een ruimtereis. ‘Acht apen hebben we de ruimte ingestuurd,’ zegt Spiridonovich trots. Het apeninstituut bereidt zich nu voor op een nieuwe taak. Met Russische ruimtevaarttuigen moeten de eerste apen ooit naar Mars worden gestuurd. ‘Mensen kunnen de straling onderweg nog niet aan,’ zegt Spiridonovich. Vol medelijden laten we de apen achter ons.

In the hills above Sukhum is a monkey laboratory, possibly the most popular tourist attraction in Abkhazia. It is a depressing place. Visitors are received by a small army of monkeys, who sit huddled in a dirty cage, carefully grooming one another. Others sit shivering on poles in separate enclosures. The buildings of the research institute loom in the background. Women in white nurses’ uniforms carry troughs, mops and brooms through the green streets. Cages protrude here and there from the buildings, and an occasional monkey hesitantly peers out at passers-by. Vladimir Spironovich is one of the researchers at the institute. He immediately discredits a story that has been circulating: in the Soviet era, monkeys were crossbred with people to create a super species with the intelligence of humans and the brute strength and dexterity of monkeys. It is a fantastical story, Spironovich admits, but he cannot emphasise enough: It. Is. Nonsense. “What we have done,” he says proudly, “is help confirm important breakthroughs in global cancer research.” Somewhere behind one of the buildings is a rotting wooden platform. This is a historical site. In this installation, monkeys from the laboratory were subjected to extensive shaking and g-forces to prepare them for space travel. “We sent eight monkeys into space,” Spironovich says with pride. The institute is now reaching for a new frontier: using a Russian spacecraft to put the first monkey on Mars. “Humans can’t yet handle the radiation on the journey,” he says. Filled with compassion, we leave the monkeys behind us.

Poverty and isolation

In the summer of 1993, the war in Abkhazia came to an end. While the Russians oversaw a fragile ceasefire, the Abkhazians unexpectedly broke through the lines and caught the Georgians off guard. The entire former ASSR, with the exception of the elevated Kodori Gorge, was conquered. Russian troops from the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS) and the United Nations Observer Mission in Georgia (UNOMIG) were deployed to guard the borders. Abkhazia was free, but had paid a high price. The war had driven out two-thirds of its citizens and the country was in ruins. It was recognised by no one, and smuggling, corruption and illegality were the only means of acquiring raw materials and products. Every peace process failed. Abkhazia had been amputated from Georgia and faced difficult years ahead in complete isolation.

One of the many abandoned houses. Sukhum, Abkhazia, 2010.

One of the many abandoned houses. Sukhum, Abkhazia, 2010.

Old Soviet mosaïque in Sanatorium 'Georgia'. Gagra, Abkhazia, 2013.

Old Soviet mosaïque in Sanatorium 'Georgia'. Gagra, Abkhazia, 2013.

In a strange twist of history, the old villa of Stalin's infamous head of security, Lavrenti Beria, was in 2007 the home of the head of UNOMIG, Ivo Petrov, a Bulgarian. Petrov makes a weary impression. It can be no easy task working in this country and this political environment. He is charged with observing the ‘ceasefire’ of 1994 and safeguarding the return of refugees. At the same time the UN troops observe the CIS troops. But observation alone makes the UN a toothless tiger. “On both sides of the border groups are always ready to fight again,” he says. “The Cherkessians from the North Caucasus will step in to help the Abkhazians at a moment’s notice, and the Georgians are easy to mobilise too. “Frozen conflicts like this one are always better than hot conflicts,” he continues. “At least there are few casualties now. But the situation remains so fragile.” Petrov tells us about the media manipulation on both sides. "By blowing small stories out of proportion, both populations stay angry at each other."

Under the leadership of the UN and others, the Abkhazians and Georgians have visited other multi-ethnic regions, to learn what coexisting can be like. These include South Tyrol, Cyprus and even Switzerland. When we put this to the Abkhazian Minister of Foreign Affairs Shamba, he laughs and quickly waves the notion away. “Of course not, where did you get that from? Yes, we were in South Tyrol, but that was for a holiday!” Petrov sighs again wearily. “Holiday! It’s his supporters. Everyone in Abkhazia is a champion of the independence struggle. If you admit to considering coexistence, you’re lost. He’ll never confirm it publicly, even though all our talks and conferences are aimed at bringing Georgia and Abkhazia together, or at least tackling the refugee problem.”

Borrowed by Abkhazians

Before we cross back over the border, or demarcation line, with Georgia we visit Ochemchira

Ochemchira

Abkhazia

, where the Russian army maintains a base and deep-sea port. Of the 25,000 pre-war inhabitants, only 5,000 remain. Almost everything is empty, the streets are as riddled with holes as Swiss cheese, the main train station is in ruins. On a dump a pig and a rat fight over the rubbish. On the boulevard are small sculptures made from the same kind of mosaic tiles as the elaborate bus stops elsewhere in the country, but here they are in ruins. We clamber into empty houses and find traces of life; an old wardrobe, a desk, broken cutlery. Under the plaster and wallpaper are old newspapers with reports on the country’s progress in 1962. It is strange to think that the original owners were killed or expelled in the war. Perhaps they now live just ten kilometres to the south, in the Georgian town of Zugdidi.

Ochemchira

Abkhazia

, where the Russian army maintains a base and deep-sea port. Of the 25,000 pre-war inhabitants, only 5,000 remain. Almost everything is empty, the streets are as riddled with holes as Swiss cheese, the main train station is in ruins. On a dump a pig and a rat fight over the rubbish. On the boulevard are small sculptures made from the same kind of mosaic tiles as the elaborate bus stops elsewhere in the country, but here they are in ruins. We clamber into empty houses and find traces of life; an old wardrobe, a desk, broken cutlery. Under the plaster and wallpaper are old newspapers with reports on the country’s progress in 1962. It is strange to think that the original owners were killed or expelled in the war. Perhaps they now live just ten kilometres to the south, in the Georgian town of Zugdidi.

Empty house. Ochamchire, Abkhazia, 2007.

Empty house. Ochamchire, Abkhazia, 2007.

Nina. Ochamchire, Abkhazia, 2007.

Nina. Ochamchire, Abkhazia, 2007.

The current residents have painted Borrowed by Abkhazians in large letters on a block of flats on Lenin Street. We meet Nina, a young girl eager to practise her English with us. She invites us to her house for lunch. “What are Georgians like?” she asks, curious about our adventures in the Georgian capital. When we say that the Georgians we have met so far have been nice people, she looks at us in disbelief. She was very young during the war. She has never met a Georgian and only knows them as bloodthirsty monsters from the history lessons at school. Her parents may talk to us about Tbilisi and Georgia, but evidently never do so with their children.

Hundreds of thousands of refugees

Destroyed train bridge on the border of Abkhazia and Georgia. Shamgona, Georgia, 2010.

Once in Georgia, we are immediately asked to report back to the Georgian Ministry of Conflict Resolution. The Georgian regime is young and ambitious and wants the best possible international press it can get. Saakashvili has repeatedly said during his time in office that he wants to unite Georgia again. Whether a visit by the Western press to Abkhazia will help him achieve this is something they are still not entirely convinced of in Tbilisi. So to visit Abkhazia, you first need permission from the Georgians.

The Deputy Minister of Conflict Resolution, Ruslan Abashidze, is a refugee from Abkhazia himself. “If you visit Gagra in the future, I’ll be the city’s democratically elected mayor!” he jokes half seriously. “The Abkhazians have to choose. They’ll never be independent with Russia as a neighbour. The Russian influence in Abkhazia is significant, ranging from Abkhazian political appointments to military and economic influence. Many people in Abkhazia are addicted to Russian support. Abkhazia has to choose, either to become an autonomous unit within small Georgia or a small and silly part of large Russia.

“What we’re going to do now is to build mutual trust. We want to renovate schools and rebuild hospitals and infrastructure in the affected regions of Abkhazia.” With courage born of despair, Abashidze does his best to convince us. “Of course we’ve made mistakes. It was a cruel war, but ultimately we were all victims of the system. The situation is so complicated, but we’re looking for a good solution. Look outside, see how Georgia is changing! We’re offering Abkhazia contact with the West. The choice is theirs: join us or follow in Russia’s footsteps.”

Destroyed train bridge on the border of Abkhazia and Georgia. Shamgona, Georgia, 2010.

Once in Georgia, we are immediately asked to report back to the Georgian Ministry of Conflict Resolution. The Georgian regime is young and ambitious and wants the best possible international press it can get. Saakashvili has repeatedly said during his time in office that he wants to unite Georgia again. Whether a visit by the Western press to Abkhazia will help him achieve this is something they are still not entirely convinced of in Tbilisi. So to visit Abkhazia, you first need permission from the Georgians.

The Deputy Minister of Conflict Resolution, Ruslan Abashidze, is a refugee from Abkhazia himself. “If you visit Gagra in the future, I’ll be the city’s democratically elected mayor!” he jokes half seriously. “The Abkhazians have to choose. They’ll never be independent with Russia as a neighbour. The Russian influence in Abkhazia is significant, ranging from Abkhazian political appointments to military and economic influence. Many people in Abkhazia are addicted to Russian support. Abkhazia has to choose, either to become an autonomous unit within small Georgia or a small and silly part of large Russia.

“What we’re going to do now is to build mutual trust. We want to renovate schools and rebuild hospitals and infrastructure in the affected regions of Abkhazia.” With courage born of despair, Abashidze does his best to convince us. “Of course we’ve made mistakes. It was a cruel war, but ultimately we were all victims of the system. The situation is so complicated, but we’re looking for a good solution. Look outside, see how Georgia is changing! We’re offering Abkhazia contact with the West. The choice is theirs: join us or follow in Russia’s footsteps.”

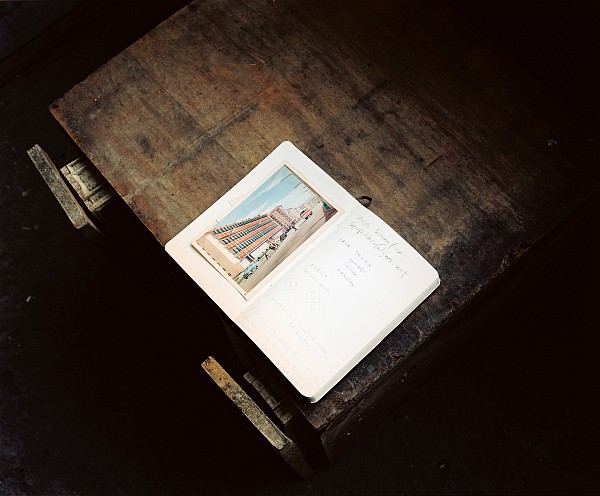

Postcard of the old Abkhazia Hotel in Tbilisi, which since the war in 1993 has housed refugees. Tbilisi, Georgia, 2007.

Postcard of the old Abkhazia Hotel in Tbilisi, which since the war in 1993 has housed refugees. Tbilisi, Georgia, 2007.

Abashidze is certainly not the only Abkhazian refugee in Tbilisi. Countless hotels, apartment buildings and student flats have been owned by refugees from Abkhazia and Tbilisi

Tbilisi

Georgia

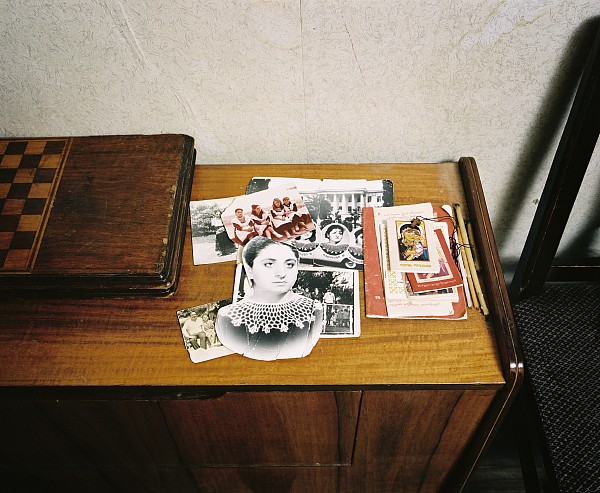

since 1993. In the old centre of Tbilisi we meet Papuna Papaskiri. He works as a designer for an advertising agency and is trying to launch a career as an artist. “I was one of the last people to flee Sukhum in 1993,” he says. “We first tried to get away via the airport, but an aeroplane that was taking off was shot down before our eyes. It was hell. We fled with thousands of others into the mountains. Through the Kodori Gorge we finally arrived in Svaneti in Georgia.” Papuna’s canvases, home-made furniture and photos of Abkhazia litter his apartment. “I couldn’t take anything with me from our house in Sukhum. I asked all my family members in Georgia for photos they had been sent, or of holidays they had spent with us. I now have a real picture of my youth again.”

Tbilisi

Georgia

since 1993. In the old centre of Tbilisi we meet Papuna Papaskiri. He works as a designer for an advertising agency and is trying to launch a career as an artist. “I was one of the last people to flee Sukhum in 1993,” he says. “We first tried to get away via the airport, but an aeroplane that was taking off was shot down before our eyes. It was hell. We fled with thousands of others into the mountains. Through the Kodori Gorge we finally arrived in Svaneti in Georgia.” Papuna’s canvases, home-made furniture and photos of Abkhazia litter his apartment. “I couldn’t take anything with me from our house in Sukhum. I asked all my family members in Georgia for photos they had been sent, or of holidays they had spent with us. I now have a real picture of my youth again.”

Papuna Papaskiri. Tbilisi, Georgia, 2010.

Papuna Papaskiri. Tbilisi, Georgia, 2010.

Old photos from Abkhazia. Tbilisi, Georgia, 2010.

Ruslan Abashidze

"We’re offering Abkhazia contact with the West. The choice is theirs: join us or follow in Russia’s footsteps.”

Old photos from Abkhazia. Tbilisi, Georgia, 2010.

Ruslan Abashidze

"We’re offering Abkhazia contact with the West. The choice is theirs: join us or follow in Russia’s footsteps.”

It took Papuna and his family seven days to cross the mountains. “It was a death march. Many people died on the side of the road. We survived by sleeping close to the fire. Even so, every morning my hair was frozen. It was indescribable. There were wild animals, we were robbed by the Svans, the mountain people who live there. When we eventually reached Georgian villages again, Gamsakhurdia had arrived and brought the civil war with him. My mother had, out of a kind of primitive instinct, stuffed all her pockets with mwaba, a sort of candied fruit. That kept us going.”

Papuna also ended up in a refugee apartment with his family. His parents still live there. “It is impossible to develop yourself in a place like that. With the best will in the world, you can’t study there, you can’t work or think there. It’s crowded, dirty and noisy. Many friends of mine are dead, often as a result of excessive drinking or drugs. I almost went the same way. I had to pull myself up by my boot straps. It was my painting that got me the job at the advertising agency and enabled me to rent this house. That was my salvation.

Papuna Papaskiri

“I still think of Abkhazia every day.”

“I still think of Abkhazia every day,” he says. We have just eaten an improvised breakfast of bread, cheese and cucumber, and are now sampling his homemade white wine. “Night after night I watch films about Abkhazia on YouTube. Facebook is full of series of photographs and discussion groups about Sukhum and Gagra, for instance. No one will ever stop missing Abkhazia. It’s a different place, there’s a certain magic attached to it. The way life there was lived no longer exists in Georgia.”

Abkhazia

General map

was still in the tongue-twisting position of being facto independent but de jure Georgian territory. In August 2008, however – while the then Prime Minister Putin, US President George W. Bush and other heads of state enjoyed the Beijing Olympics – Russia and Georgia declared war on each other. Some expressed outrage, saying that this violated the Olympic Truce, which calls for a global cessation of hostilities during the Games.

Less than a month later, Russia recognised Abkhazia and South Ossetia as official, de jure and de facto countries. Nicaragua, Venezuela, Vanuatu, Nauru and Tuvalu followed suit shortly after.

Georgian weaponry in Abkazia, remnants of the 2008 War. Kodori, Abkhazia, 2010.

Over the past decade, the English NGO Halo Trust has completely cleared Abkhazia of mines and loose ammunition.. Kodori, Abkhazia, 2010.

Georgia

Under its revolutionary president, Mikheil Saakashvili, wanted independence, a seat in NATO and even European Union membership. Russia, however, still regards the former Soviet Union as its natural sphere of influence. The Baltic states may have been relinquished, but the others are expected to fall in line. Russia sees itself as a big brother, a father figure even in relation to its former vassal states. For an energetic and ambitious government such as Saakashvili’s, this was a dramatic, old-fashioned and outdated way of thinking. It would consider nothing less than an equal relationship with Russia. But decades of hurt and resentment in Georgia meant that Russia could do little right. In the year prior to the war, the airspace above Georgia was a game of cat and mouse between Russian manned and unmanned military aircraft and Georgian rockets. In the North Caucasus, Russia assembled troops and held exercises for land invasions.

One of Saakashvili's main agenda items was the reintegration of three areas lost in the 1990s: Adjara, Abkhazia and South Ossetia. Adjara, the region around the port city of Batumi, was quickly regained. The corrupt local ruler immediately flew to Moscow. But South Ossetia

South Ossetia

– a patchwork of Georgian and Ossetian villages, peacekeeping troops and complex family ties – and Abkhazia were not quite as easy. Saakashvili transformed the few villages over which he still had control in the republics into Georgian model villages, generously assisted by a variety of international NGOs and donors. New schools and banks with ATM machines were built, non-corrupt (traffic) police were installed and pensions and benefits were paid on time. That was all expertly destroyed, during and after the war in 2008. Out of the conflict was born South Ossetia, a completely unviable republic of less than 60,000 inhabitants, separated from Georgia by fences and barbed wire. Abkhazia [meanwhile] has been a viable country since the first war in 1993.