Meatballs with cream three times a day

The train journey from places like Murmansk and distant Siberia takes several days.

In the early spring, summer and autumn hundreds of thousands of Russians flock to Sochi to spend time in a sanatorium. The majority of visits are organised through municipalities, factories, employers or unions but individual bookings are on the rise.

The train journey from places like Murmansk and distant Siberia takes several days. But the first glimpse of the Black Sea, and with any luck a leaping dolphin, the small pebble beaches lined with large white hotels, palm trees and tea plantations make it all worthwhile. Overheated and weighed down with luggage, they crowd the tiny train stations. Lazarevskoye, Loo, Dagomys

Coast of Sochi

Sochi region

... The majority alight in Sochi, at a beautiful, light-filled station built in Stalin's Empire style. They are met by buses and marshrutkas, small private buses, that take them to their final destination.

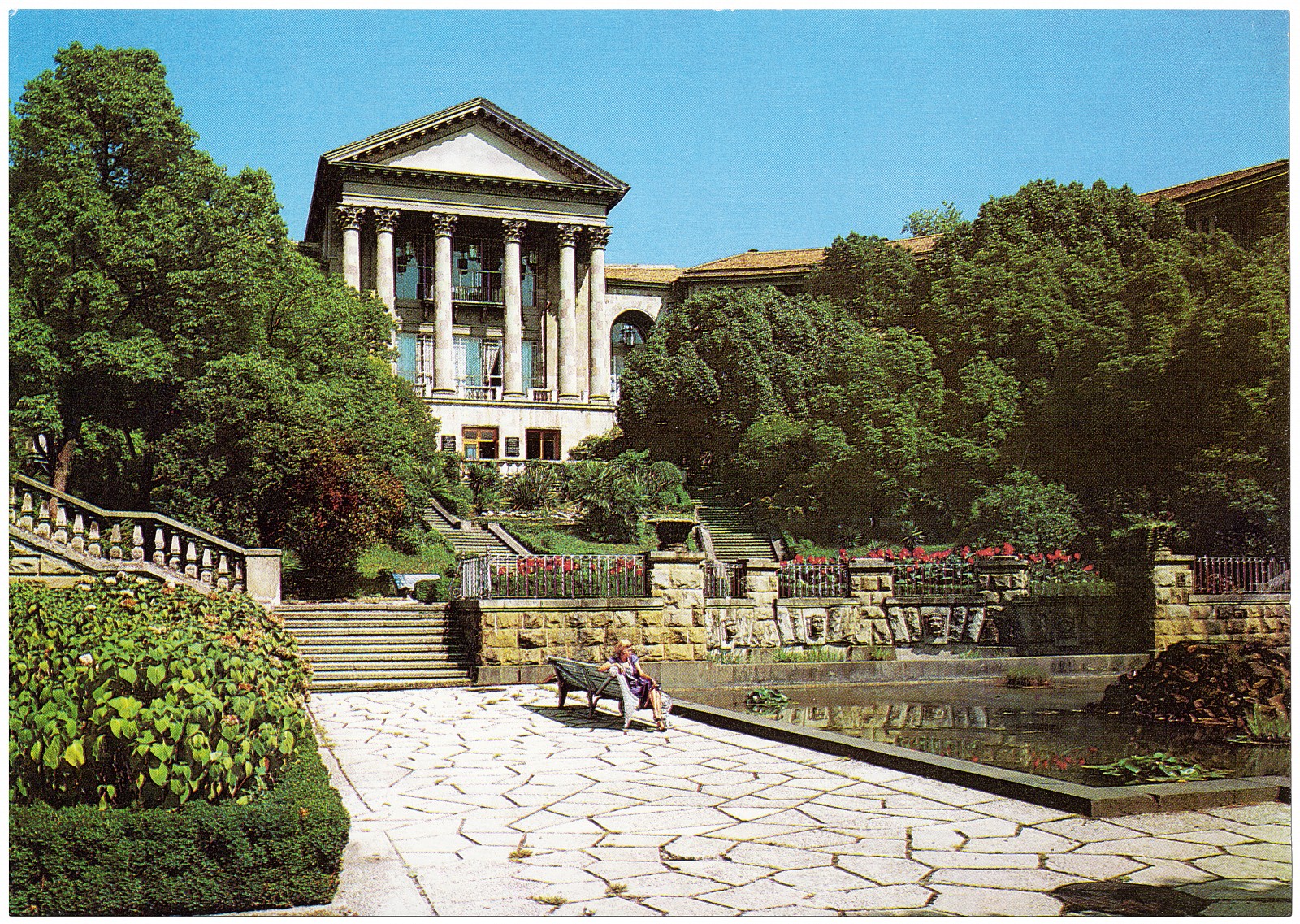

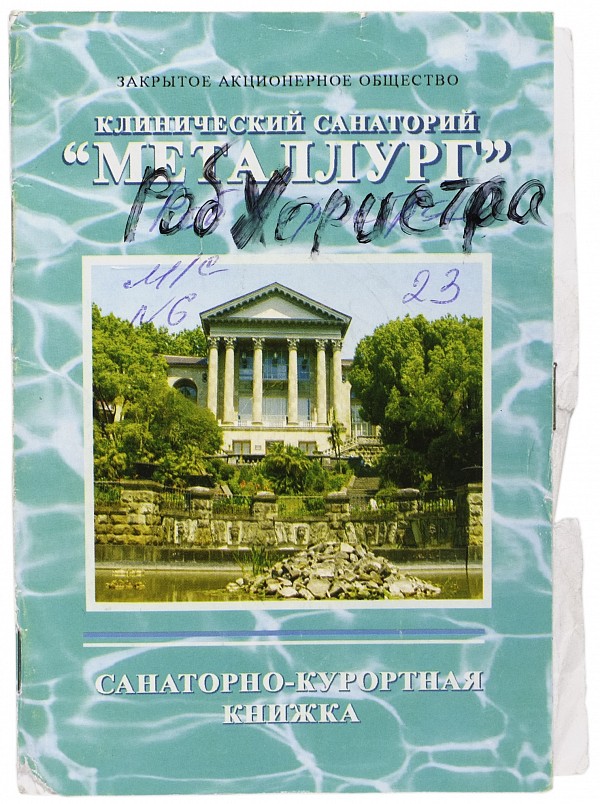

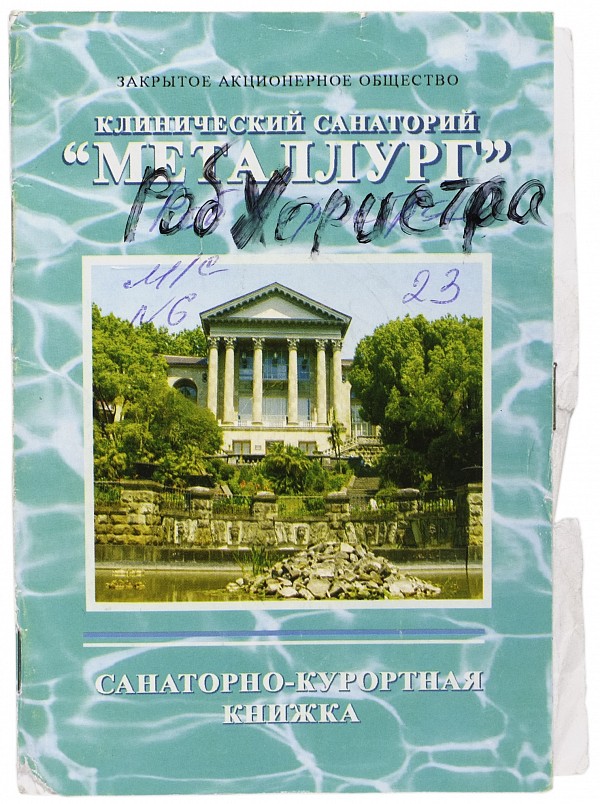

The most prominent sanatoria and hotels can be found on Sochi's longest road, Kurortnaya Prospekt (‘Sanatoria Road’). Of these, Sanatorium Metallurg is one of the finest. In 2009 we decide to try our hand at embedded journalism and sign up for a two-week stay at Metallurg.

From the road, stately steps lead up the palace in the distance. Throughout the park is a network of paths with coloured arrows, each serving a different purpose. There is a conditioning path, a digestive disease path, a cardiovascular path. Hidden in the grounds is a swimming pool, elaborately decorated with socio-realist scenes, which is filled every day with several thousand litres of filtered seawater. In the sanatorium itself, we embark on a quest for the correct papers. We walk from office to office and several hours later have accumulated a stack of coupons, booklets, brochures and tour folders. “This is normally all arranged in advance,” the lady at reception apologises.

Coast of Sochi

Sochi region

... The majority alight in Sochi, at a beautiful, light-filled station built in Stalin's Empire style. They are met by buses and marshrutkas, small private buses, that take them to their final destination.

The most prominent sanatoria and hotels can be found on Sochi's longest road, Kurortnaya Prospekt (‘Sanatoria Road’). Of these, Sanatorium Metallurg is one of the finest. In 2009 we decide to try our hand at embedded journalism and sign up for a two-week stay at Metallurg.

From the road, stately steps lead up the palace in the distance. Throughout the park is a network of paths with coloured arrows, each serving a different purpose. There is a conditioning path, a digestive disease path, a cardiovascular path. Hidden in the grounds is a swimming pool, elaborately decorated with socio-realist scenes, which is filled every day with several thousand litres of filtered seawater. In the sanatorium itself, we embark on a quest for the correct papers. We walk from office to office and several hours later have accumulated a stack of coupons, booklets, brochures and tour folders. “This is normally all arranged in advance,” the lady at reception apologises.

Rob's treatment diary for Sanatorium Metallurg. Sochi, 2009.

Rob's treatment diary for Sanatorium Metallurg. Sochi, 2009.

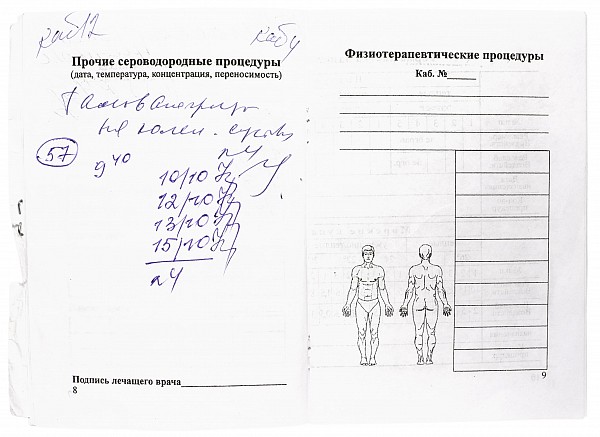

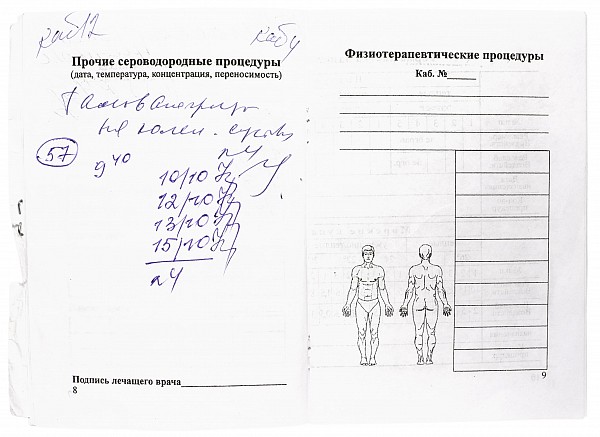

Notes in treatment diary. Sochi, 2009.

Notes in treatment diary. Sochi, 2009.

The all-inclusive holiday could have been invented in Sochi.

The all-inclusive holiday could have been invented in Sochi. The vouchers, putyovkas, handed out by companies, unions and government bodies offer employees a package that includes meals, film screenings, treatments and accommodation. According to the nursing staff, a treatment in Sochi is only beneficial after at least two weeks rest, an unheard of luxury.

The pace of life in the sanatorium is leisurely. The guests, possibly patients, amble from doctor's office to herb tea cafe, from sulphur bath to treatment room. We feign back and heart problems and answer 'yes' to all the options that are offered to us. We want massages, bubble baths, electrically charged clay treatments, herbal tea and yes, we definitely want to attend the 'honey and herbs from the Caucasus' information evening. Followed by a disco upstairs.

Everything seems to be geared towards health and fitness, the walks in the park and morning exercises included. But like most hospitals, the three daily buffet meals somewhat hamper progress. From the kitchen issue bowls of rice pudding, greasy porridge, potatoes in all shapes and sizes, pasta, meatballs and fish submerged in fat. The salad bar looks healthy, but the Russian penchant for smetana, a sort of sour cream, should not be underestimated. Excessive amounts of the cream are mixed into the salad until a smetana-salad ball is all that remains. Staff come and go with bowls of the stuff. Dessert is cakes and biscuits filled with sweet, sticky jam.

Bandits from Moscow

Viktor Alexeevich on the private beach of sanatorium Metallurg. Sotsji, 2009.

Viktor Alexeevich on the private beach of sanatorium Metallurg. Sotsji, 2009.

On the small private beach, at the bottom of a steep staircase where our putyovkas are checked, we meet Viktor Alexeyevich. A retired shipbuilder from Murmansk, he has happily made use

of the gratis opportunity to relax in Sochi for years. “Sochi used to be much prettier,” he says. “These days crooks from Moscow come here to build and sell skyscrapers and apartments, although it used to be such a small, lovely town. You can’t even see the sanatorium from the beach anymore. Still, it’s better than Murmansk.”

Siraj Sartakati

“Don’t you find it terribly boring here?"

“Don’t you find it terribly boring here, with all those old people and outdated treatments?” Siray Sartakati, the 28-year-old marketing manager of Metallurg, asks us. “Look at this beautiful building. Shouldn’t there be clubs, bars and terraces?” On the contrary, we have been in the monumental sanatorium for a week and are having a great time among Russia’s elderly and infirm. Every day we are massaged, drink mineral water and revolting tea and bathe for 20 minutes in a radon bath. Wonderful. In the evening the sanatorium organises a disco and karaoke. Then all hell breaks loose, as the elderly guests throw themselves around the dance floor as if possessed. It is an entertaining spectacle.

A miniature Versailles

Siraj Sartakati

“Everything has to be luxuriously finished.”

“Everything has to be luxuriously finished,” says Siray, “made from real European materials. The atmosphere has to remain the same, but the quality has to be significantly improved.” He taps the window frames, walls and bronze doorknobs. The owner, the Association of Unions, has appointed him to overhaul the institution. “It all has to be finished by 2014, in time for the Winter Olympics. We'll then no longer be a sanatorium but a five-star hotel.” Siray is sitting on a gold mine. Metallurg is a miniature Versailles, where one can descend through extensive gardens, down endless steps past fountains and ponds to the private beach. The canteen is a stately ballroom. It is still a palace for the proletariat, as it was once intended, but not for much longer if Siray has his way.

Sanatorium

Now that new managers are trying to save the buildings and parks and to tap additional sources of tourism, the old proletariat may well miss out. If the transition continues, Russia’s growing middle class and elite will holiday here in the future. Without wanting to damage the old image, incidentally. For that the Sochi brand is still rock solid. Sanatorium USSR is already making a brave attempt, and has retranslated the four letters from Union of Soviet Socialist Republics to make it mean Friendly, Service Oriented, and One Hundred Per Cent Relaxing.

Siraj Sartakati

"For 2014 we’ve changed this town beyond recognition."

But most Russians with money – not to mention foreigners – prefer cheap, exotic destinations such as Turkey and Egypt over the Black Sea coast. “The Soviet mentality and rudeness that still prevail here scare people away,” says Siray. “If the staff can’t adapt, they’ll be fired. But for 2014 we’ve changed this town beyond recognition.”

Pumping music

Guests dancing in summer cafe Proletarsky, at the boulevard. Sochi, 2011.

Guests dancing in summer cafe Proletarsky, at the boulevard. Sochi, 2011.

Tourist Sochi

Respectable families and drunks carrying large bottles of beer walk side by side.

is not quite as tranquil as the grounds of Sanatorium Metallurg. In the coastal areas, the smell of sunscreen, sweat, alcohol and roasting meat pervades the air. On the beaches, perspiring men with baskets of blackberries, popcorn and corn advertise their wares. Respectable families and drunks carrying large bottles of beer walk side by side. In the streets and alleys behind the beaches, clouds of smoke from grilling shashlik drift upward. On the promenades, voluptuous girls lure visitors to the attractions: throwing darts at balloons, shooting guns, having the skin on your feet nibbled off by special fish, parasailing, banana boating, having your photo taken with a wild African – the options are almost endless.

'A bunch of white roses, love lingers in each petal.' Like an amusement park, the sickly sweet music is fired on the million or so tourists crowding the long coastline around Sochi. It is inescapable. If there is no singer performing his tricks, the music pounds from huge speakers, and if there are no speakers, the music blares from several televisions. The same songs are played everywhere. You could fill notebooks with the number of times Biz Tebya (Without You) is played.

Chansons and Sochi belong together like sausage and mash.

Chansons and Sochi belong together like sausage and mash. Those looking for a relaxing holiday would do well to come in the winter, because in the summer Sochi is the capital of the Russian chanson. Chansons are Russian ballads, but the comparison with French chansons is only partial. The songs have their origins in the age-old Russian tradition of labour camps and prisons. They are tragic songs, about lost loves, life on the taiga and the longing for home. These days they are usually accompanied by a heavy disco beat and occasionally even a dash of techno. The modern Russian chanson is also called popsa, giving disco, house and pop music influences their own place in the genre. The chansons of past and present are often remixed into house music numbers which young and old can dance and sing along to.

Seniors refuse to be banned from the dance floor.

Young and old, because seniors refuse to be banned from the dance floor. With skirts hitched up and breasts strapped down, davay, the women are off. Older men excel at dancing as though they have just sat in a red ants’ nest. Small children are hoisted onto shoulders or wrap their arms around a partner their own size. After each song the dancers shuffle back to their tables, but often turn around again midway when they hear the beat of the next number.

Russia

General map

has reached the final round in its bid to host the 2014 Winter Olympics, together with South Korea’s Pyeongchang and Austria’s Salzburg. "Sochi is a unique place," Putin says in carefully rehearsed English. “On the seashore you can enjoy a fine spring day, but up in the mountains it's winter. I went skiing there six or seven weeks ago and I know, real snow is guaranteed.”

President Vladimir Putin

“Real snow is guaranteed.”

He concludes his speech with a few sentences in French, smiles to the room and returns to his seat visibly satisfied. Salzburg is eliminated in the first round of voting, putting Pyeongchang in first place. Sochi wins in the second round. Putin's diplomacy has worked. Spontaneous celebrations erupt and fireworks are set off in cities across Russia, state media reports.

The railway goes right past the pebble beach of Kurortny Gorodok. Adler, Sochi Region, 2011