Around €2 billion is being spent on securing the 2014 Olympics

Russia

General map

. At least that is the figure most often quoted. In the mountains above Sochi, the heavy helicopters of the FSB – also responsible for border control – circle above the valleys and peaks where the Games will be held. Further into the mountains an electronic curtain has gone up, which is impossible to penetrate without being detected. Local activists reported in 2012 that wild boar had set off the alarm – the automatic system is apparently unable to distinguish them from humans. The boar were supposedly shot, but this is only one of the many hard-to-verify reports about the Olympics, their financing and security.

Several hundred kilometres away, on the border between Karachay-Cherkessia and the unstable, violent republic of Kabardino-Balkaria

Kabardino-Balkaria

Russia

, a second internal border is said to have been erected. Behind it, security and human rights have deteriorated significantly in recent years.

The danger of a terrorist attack has hung over the Olympics like the sword of Damocles since 2007.

The danger of a terrorist attack has hung over the Olympics like the sword of Damocles since 2007. Some of the many attacks in the North Caucasus seemed to be barely disguised exercises for Sochi. As in February 2011, when armed militants on the slopes of Mount Elbrus, Europe's highest mountain, shot at a bus of Russian skiers, killing four. The same day, the militants also sabotaged the ski lifts by attaching bombs to the cable cars, bringing down around 30 of them. Or as in February 2012, when heavy fighting broke out between Russian and Chechen army and police units on one side and several rebel cells on the other. The fighting took place in deep snow, leading news reports to speculate that it was also in preparation for Sochi.

No satanic Games

In 2013, Dokku Umarov, the self-proclaimed leader of the insurgency against Russia and the local pro-Russian regimes, spoke out about the Olympics in Sochi.

Dokku Umarov "We, the Mujahedeen, must do all we can to stop these Games."

He called on all Islamic militants in the region not to allow the 'satanic Games' to go ahead on the graves of their ancestors. Umarov’s Caucasian Emirate, which sees itself as the successor of the independent Chechen regimes and fighters such as Shamil Basayev, is believed to be behind the Moscow metro bombings in 2010 and the bomb at Domodedovo Airport in 2011. In addition, cells of this organisation are responsible for many smaller, more local attacks on civilians, shops, politicians and other targets in the North Caucasus itself. "We, the Mujahedeen, must do all we can to stop these Games," Umarov said.

In August 2013, Emir Saladin, the leader of a previously unknown group of Russian and Caucasian jihadists volunteering in Syria, appealed to fighters to wage holy war back home, including in Moscow and Sochi.

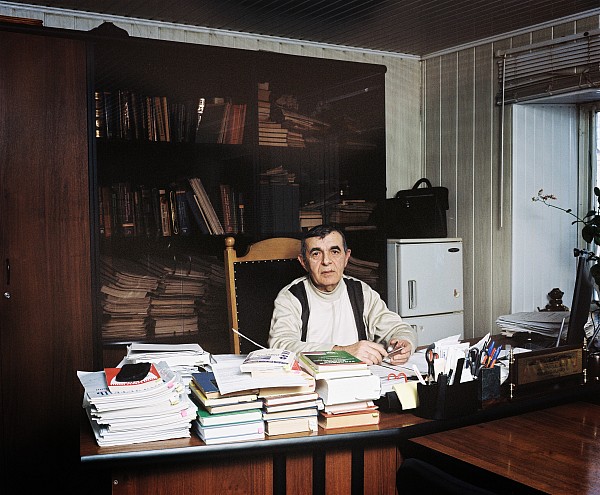

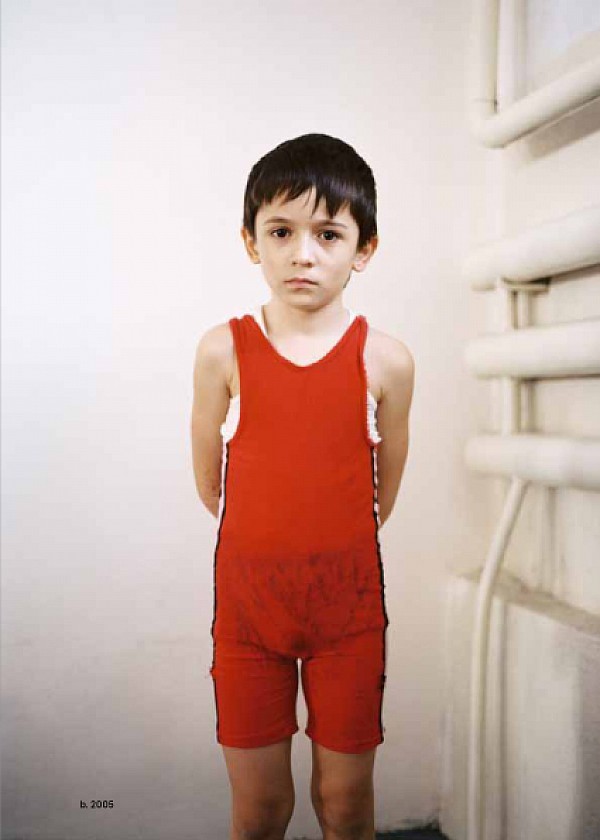

Military checkpoint in Dagestan. In Dagestan some villages and cities are under a permanent KTO-regime, a counter-terrorist regime – like emergency rule. It means that all houses, cars and persrons can be searched by police and security forces. People can always be locked up without any warrant.

The Chechen wars weakened the Caucasus. Violence, anarchism, terrorism and corruption have destroyed all the early ʼ90s dreams of restoring local traditions and achieving greater independence and freedom. Out of this period of chaos and strife a new phenomenon has emerged, something that Russian and local leaders are only too happy to label as alien to the Caucasus, but which simultaneously underlines the parallels with the First Caucasian War: Islamic radicalism. Local, traditional Islam barely had a chance to recover in the years after the atheistic Soviet Union before missionaries from the Middle East and Afghanistan introduced new, more radical and orthodox strands. These thrive here, just as the Muridism of Imam Shamil and his followers struck a chord during the First Caucasian War. Linked to this radical Islam is a new movement, arising from the international jihadists and pro-independence militias of the Chechen wars. The wars in the Caucasus may officially be over, but the Second Caucasian War continues, in an unremitting struggle for control of the rugged mountains.

The Chechen wars weakened the Caucasus.

The Second Chechen War spilled over the borders of Chechnya much more frequently than the first war in the 1990s. Rather than a struggle for national liberation, this conflict quickly turned into guerrilla warfare, fought by militias more motivated by ideology than nationalism. Their goal was to establish an independent Chechnya, preferably a Caucasian Islamic state able to join radical Islamic movements elsewhere in the world, including Al-Qaeda and the Taliban, with whom they were in contact.

Indifference

Pyatigorsk is located between Cherkessia and Nalchik, on the Transcaucasian M29 motorway

Transcaucasian M29 motorway

The North Caucasus

. Pyatigorsk is the main city in this part of Russia. The words ‘Spa town of the Caucasus’ are proudly displayed on flags and banners. Numerous memorial plaques adorn the walls of houses where the famous writers Pushkin, Lermontov and Tolstoy lived or stayed. Five mountain peaks are visible around the city (Piatigorsk literally means ‘five mountains’), marking the gateway to the Caucasus. Yet no other city has turned its back on the Caucasus quite like this one.

It is raining and on a terrace at Prospekt Kirova, tourists shelter under a canopy with mugs of beer and freshly roasted shashlik. Prospekt Kirova is on the road between the sanatoria and baths located higher up, and the shops and restaurants in the centre. A small tram creaks and groans on its descent. A group of girls dressed in tiny shirts and hot pants runs squealing up the slope. A trio fights good humouredly over a shared umbrella. Everyone is relaxed. It is a scene unimaginable in the North Caucasian republics.

The Caucasus and their mountain peoples are best avoided.

This indifference infuriates the Caucasian militants, inciting them to carry out their horrific attacks. In a video shot by the captors in Dubrovka Theatre, the following phrase stands out: “Russians are unaware of the innocent people – the sheikhs, the women, the children and the weak – who lose their lives in Chechnya. That’s why we’ve taken this approach. For the freedom of the Chechen people it doesn’t matter to us where we die; that’s why we’ll die here in Moscow. And we’ll take the lives of hundreds of sinners with us. Our nationalists die, and they are called terrorists and criminals. Russia is the real criminal.” In an interview, Shamil Basayev referred to himself as a bandit and terrorist, but asked the question: how would you refer to the Russians? “The Russians have killed 40,000 of our children,” he said. “All Russians are guilty because they gave their consent by remaining silent.” He referred to the theatre siege as “a glimpse of the charms of war for the Muscovites”.

Shamil Basayev "Russia is the real criminal.”

This explains why since 2000 the violence has spread from the North Caucasus into Russia, including Moscow, Krasnodar and Piatigorsk. Trains to Mineralny Vody and Essentuki have been blown up close to Piatigorsk and bombs have been set off within the city itself. Beyond the terrorist attacks listed earlier, however, most violence still occurs within the North Caucasus. Several times a month bombs explode in one of the republics, or a police station or government building comes under heavy fire – from troubled Dagestan in the east to the more peaceful, but certainly not unscathed Karachay-Cherkessia.

Security camera caught an earlier bomb attack on the liquor store on video.

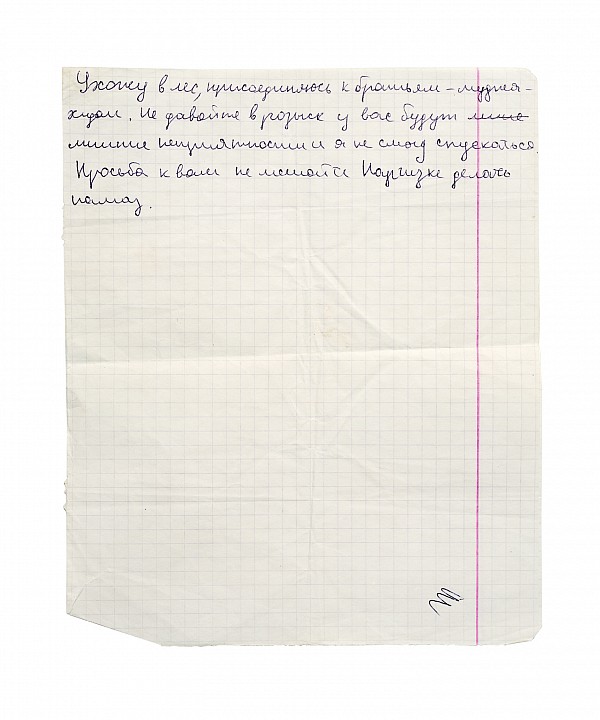

Close to the Chechen border is the village of Ordzhonikidzevskaya. Beslan’s family business extends to a car dealership, a car wash and a large off-licence, although the off-licence no longer exists. Two days before our visit, it is blown up by Islamic terrorists.

“I saw it happen,” Beslan says. “We were standing talking just down the street. It was the evening. 21.47 to be precise.” He explains how two people entered the shop, where four customers and two salespeople were busy with the drinks. The terrorists were wearing masks and started shooting bullets at the ceiling. “The police said that they were hooligans, but that’s typical of the Caucasus,” he laughs. While the men were shooting, they stuck a bomb to the counter. Beslan had 12 cameras around his shop, which recorded everything.

The day after the explosion, trucks arrived and drove back and forth to the rubbish dump 11 times. New bricks have now been delivered. “This is the fifth time in two years that our shop has been blown up,” says Beslan. “It’s starting to feel like a routine.”

He explains that the boyeviks harass him continually. “Sometimes they come and demand money, but we don’t want to give in. We tell them that we pay taxes. We have all the paperwork to prove that we’re legally allowed to be here and to trade. We say it as publicly as possible so that everyone knows the position we’re in. This is a small town and news travels fast.”

The terrorists have spies everywhere, he tells us, from young children to old grandmothers. Every family member is loyal to a son, brother or cousin, even if they do not agree with what they are doing. “The terrorists are against off-licences because they support Islamic sharia,” says Beslan. “It’s primarily poor boys who go into the woods because they can make good money. We’re vulnerable, and they know that.” He knows precisely who is behind the attack. “An old classmate of mine shot my brother-in-law. That classmate was also a terrorist, but he was killed when a bomb he was planting in the post office went off prematurely. They’re complete hooligans,” Beslan emphasises for the second time. “Misguided idiots who are too lazy to find steady work.”

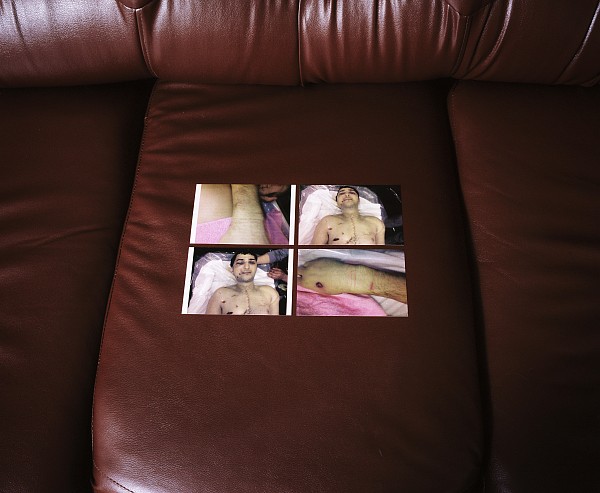

Terror in the North Caucasus

The hostage crisis at School No. 1 in Beslan, described in chapter IV, is the most extreme example of the local attacks. In Vladikavkaz, a bomb exploded at the central market in 1999, 2008 and 2010. In Kizlyar, Dagestan, two suicide bombers blew themselves up in front of the police and FSB offices. In 2012, a brother and sister blew themselves up at a checkpoint in the capital Makhachkala, killing dozens. These are just a few examples from an endless, relentless series of terrorist attacks. The war and bombings create a vicious cycle of violence. Following the end of the conflict in Chechnya, it is notable that local leaders only announced successes. The press releases and statements from the time lead you to the impossible conclusion that from a maximum of 25-250 militants surviving in the mountains, several thousand have since been killed. Local governments and Moscow appear to consistently underestimate the size and thus the danger of the insurgency – whether for show, to maintain the region’s subsidies from Moscow or for some other reason.

Local election rally in honor of Russian president Putin, March 2012. all around road are blocked by tanks and heavy equipment. Local elite forces guard the event.

‘Forever with Russia’ adorns the city gates of Nalchik, the capital of Kabardino-Balkaria. In neighbouring North Ossetia, a large park has been laid as a symbol of the enduring link with Russia. In Ingushetia, the deportation monument does its best to demonstrate the country’s positive bonds with Russia. In Chechnya, triumphal arches adorned with portraits of the Chechen and Russian presidents can be found at the entrance of almost every city and village. Likewise in Dagestan, the head of the Russian president is displayed everywhere.