It was the main topic of conversation during our trips to Abkhazia

Abkhazia

General map

in 2009 and 2010: Russian tourists would rediscover Abkhazia, Europe would recognise it – and if not Europe, then at least the non-aligned countries in South America and Asia.

When we returned in 2013, Abkhazia was still only recognised by six countries. Moreover, a political dispute had erupted between the prime minister and foreign minister of the Vanuatu island nation about whether Abkhazia was recognised or not. The prime minister said it is, the foreign minister disagreed.

In addition to diplomatic recognition, the Olympics in Sochi were supposed to end Abkhazia’s isolation. The only time that actually happened was when – under dubious circumstances – two ammunition depots in Abkhazia belonging to North Caucasian terrorist groups were dismantled. The news reports that followed speculated that it was a setup by Russian security forces intent on securing the Olympics across the border, but this was never confirmed and nothing more was ever heard about the matter.

Renovations

When we visited Abkhazia for the second time in 2009, the country was still in a festive mood following Russia’s unexpected diplomatic recognition in 2008. We travelled to Pitsunda, a small seaside resort on a sandy, pine-covered peninsular. In a noisy restaurant we bumped into the town’s mayor, Beslan Ardzinba. He was celebrating his birthday, but interrupted the merrymaking to welcome us and offer us a bottle of local champagne. We spoke about the beautiful beaches, the imposing but dilapidated blocks of flats, the deserted ballroom and the crumbling billiard halls we had seen. "I know all about this, of course," the mayor said before returning to his party, "but come back in a year and everything will be different."

Beslan Ardzinba

"Come back in a year and everything will be different."

Beslan Ardzinba, mayor of Pitsunda

Three years later, nothing has changed in Pitsunda. We meet the mayor again, this time in his office. He rustles up coffee and cake, but halfway through the conversation he relocates to a traditional restaurant to continue talking over wine, chacha, cognac and mountains of meat. "We're doing everything we can to make things better and improve our service," he repeats. "But it’s taking a while. We’ve started work on the interior and hope to finish it this year." He listens as we reel off a list of all the things that still have to be done. "We’re the safest place on the planet. We invite everyone to come here on holiday. We will make it as easy for them as possible." He continues talking about laws that need to be changed to protect property, state hotels that need to be privatised but – just as in 2009 – Abkhazia’s bright future always seems to be just over the horizon, with little being done to bring it any closer. In 2013 there is still no scheduled flight or ferry service out of the country. The improvised postal service operates through Sochi, and half of all the houses and buildings in the small country are in ruins.

The former ballroom on the beach of Pitsunda, Abkhazia, 2009.

When we return four years later, nothing has changed. Pitsunda, Abkhazia, 2013.

We are a paradise

Milana Vozba

“Just imagine if it were modern and stylish.”

Milana Vozba 2013

“Just imagine if it were modern and stylish”, sighs Milana Vozba, 22. We are standing outside one of Pitsunda’s high-rise hotels. In the background the surf breaks on the pebble beach, producing a pleasant soundscape. A handful of Russian tourists enjoys the spring sun. In early March it is already 22 degrees Celsius. “These buildings damage our country’s reputation. Imagine, we have snow in the mountains and at the same time we have the sea. And can you smell the flowers?” Milana is as nationalistic as the other 200,000 inhabitants of this tiny country on the Black Sea, but she is also aware of the slow rate of change. “It’s because our country is so isolated,” she says, “and corrupt and lazy. Our climate is too temperate and our soil too fertile. But there are advantages as well. Our long isolation means that we’ve had time to reflect on who we are and what we want. Everyone knows that nature is our calling card. While Sochi is being ruined, we’ve remained a paradise.”

Milana Vozba

"We need the courage to move forward, not to look back so much.”

Milana Vozba 2010

Abkhazia's first president and leader in wartime Vladislav Ardzinba is commemorated all around Abkhazia.

Milana belongs to the generation of Abkhazians – aged between 20 and 40 – that looks outward. They have lived through the hard times at home, while abroad they have tasted open societies and education. “We respect everyone who fought in the war and we respect our elders, that’s part of our culture. Georgia still won’t officially say that it will never use violence against us again, but we need the courage to move forward, not to look back so much.”

Reinventing the country

Angela Pataraya, 25, calls herself ‘the last war generation’. “The generations behind me didn’t experience the war,” she says. “They are concerned mainly with the latest fashions and phones. My generation doesn’t care about that.” She studied international relations and spent a year in California as part of an exchange programme. She is now trying to find work with a peacekeeping NGO and frequently travels to Turkey to meet the Abkhazian diaspora, which has lived there for 150 years but might consider returning. She would, she says, that's how much she loves her country.

Angela Pataraya

"I want to think, do and dream Abkhazian. But I often think and dream in Russian and many of our traditions have been lost.”

Angela, 2010

Angela never misses an opportunity to point out how beautiful our surroundings are and how much potential they have for the country. As part of the same exchange programme she also went to Tbilisi. “Georgians are power hungry and arrogant,” she says of the experience. She doesn’t believe in any conciliation. “But hopefully we can be normal neighbours. They can come here on holiday if they want.” She was young during the war. The thing she remembers most is macaroni with sugar. “It came from some emergency rations that were distributed in Gudauta.” In the garden of a sanatorium is a small statue of a man with a video camera. “That’s my uncle,” Angela tells us. “He was shot by a Georgian sniper. We now have our independence, but it came at a price. We – the younger generation and those after us – must always remember that.” She and her peers are reinventing their country. “The Soviet Union destroyed so much. I want to think, do and dream Abkhazian. But I often think and dream in Russian and many of our traditions have been lost.”

Angela Pataraya “I hope that one day we’ll be like Japan.”

Some evenings we have dinner with Angela in Sukhum’s Japanese restaurant, one of the symbols of this recovering country. It is an unlikely place, with DJs, wealthy Abkhazians and reasonable food and drink. “I hope that one day we’ll be like Japan,” Angela sighs. “Very modern, but also loyal to our own traditions.” Her phone rings. She is called every ten minutes by men – brothers, we assume, but they could be nephews. “Security,” Angela calls them. They check whether she is all right, where she is and what she is doing. “Abkhazia is sometimes oppressive, but that’s the way it should be. I absolutely want to marry an Abkhazian man and stay here.” A few days later we are sitting in our rented flat in the centre of Sukhum. We call Angela to go over the schedule and complain that the pizza delivery service has failed for the fourth time. Once again we eat yoghurt and sausages from the late-night shop across the street. Half an hour later Angela calls us back. “Is this your house?” We hear honking. She and her security are outside. They pull a steaming pizza box from the back seat. “I told you it works,” she says proudly.

Angela promotes Abkhazia

Cold War mentality

Viacheslav Chirikba

Abkhazian Minister of Foreign Affairs is possibly one of the most hopeless positions in international politics. Only three major countries – Nicaragua, Russia and Venezuela – recognise Abkhazia, and rumours circulate that recognition by the Pacific Islands Nauru, Tuvalu and Vanuatu was the result of a deal with Russia. The hopeless position is currently filled by Viacheslav Chirikba, a balding man in his late forties. With a tiny ministry of barely 20 people behind him – little more than a corridor in a small building full of ministries – he is tasked with convincing the world that Abkhazia really exists, is viable and deserves official recognition. “It’s hard,” the minister tells us in the lobby of Ritsa, an old hotel on the waterfront of Sukhum. He is in a hurry because he has to pick up his children from day care, but decides to send his driver instead. “A bloc policy has been established. It’s as if the Cold War mentality still prevails. People think that if Russia is the only country to lend us real support, there must be something wrong with us. But our aim is to remain independent, to become a small, tourist-driven country on good terms with all its neighbours. It’s difficult to achieve, but that’s our goal.”

On the road from Sukhum to the south.

Several years ago, Chirikba’s predecessor still believed that a contemporary version of the domino theory would guarantee recognition of his country. After Russia recognised Abkhazia in 2008, a young Maksim Gvindjia travelled the world and saw the whole of Latin America fall for his charms. Chirikba interrupts me when I mention this. “Yes, and then the European Union came along and told everyone – South America, Belarus, Kazakhstan – that it would impose sanctions on them if they recognised us.” His frustration is audible. “There’s an on-going crusade against Abkhazia. That’s despite the fact that recognising us would be beneficial for Georgia as well. The border could be opened again and refugees could travel back and forth.” His use of the word travel is no accident. Except in the south, Chirikba does not see Georgian refugees returning permanently to Abkhazia. “Of course we are still fighting for recognition, but it is now perhaps more important to disseminate accurate information, to show that we are no longer a conflict zone, to organise exchanges and kick start our economy.”

A country in ruins

It is more or less the same story we heard several years ago. Our tour of the country is also a monotonous experience. Tkuarchal, a mining town in the hills in the southeast of Abkhazia, for instance, is still in ruins. Only when we return home and compare the photos from then and now do we see that a few, almost imperceptible changes have taken place.

Tkuarchal, 2010

The cover of our 2010 book & the cover of its reprint in 2013. No change.

Tkuarchal, 2010

If you look well, all of a sudden you see a new road appeared. it doesn't look too new, but we guess it should be a new one, regarding the 2010 picture.

The next president

2013 & Ainar, 2010 (on the picture)

In Tkuarchal’s small school, we meet Ainar again. In 2010, three years earlier, he wanted to be president of Abkhazia. He still wants to be president, but in order to make that happen he is now learning a skill: singing. He can sing with the best of them, his teacher confirms. Only in the Kodori River do we see any activity. To the dismay of many Abkhazians – nature is viewed as the country's unique selling point – the river has been partially excavated to supply Sochi with gravel and building materials. The choice facing this parochial country so desperate to define itself is perhaps a cynical one: continuing to live in an isolated paradise or gradually opening up to the often less-than-sustainable global economy.

Refugees

In the last few years, a number of refugees from Georgia have returned to the Gali district, the south-eastern part of Abkhazia inhabited by the Mingrelians, a Georgian ethnic subgroup. NGOs regularly point to the violations of the rights of the Mingrelians, including native-language education and fair trails, at the hands of authorities largely appointed by the central government in Sukhum. Still, the Mingrelians say, this is preferable to living in the cramped refugee flats and old schools in Georgia.

The border river Inguri between Abkhazia and Georgia.

A man crosses the impovised border from Georgia to Abkhazia. On the other side a Russian border post awaits him.

Anna, the daughter of Ketevan in chapter II, lives in the biggest refugee flat of Tbilisi.

In 2012 a new government came to power in Georgia. Saakashvili was more or less reduced to the role of a ceremonial president. The new leader, billionaire Bidzina Ivanishvili, promised to strengthen ties with Russia. At the same time he offered to resume direct talks with Abkhazia and South Ossetia. But under the military and political protection of Russia, the breakaway provinces rejected his advances, saying they would only consider full independence from and equality with Georgia. It remains to be seen whether a Georgian prime minister or president – faced with more than 200,000 refugees from these regions – will ever agree to this. Georgia’s overtures to Russia fared little better. A few Georgian products, such as water and wine which have been embargoed since 2008, are once again allowed across the border. But in an interview with the Georgian TV channel, Rustavi-2, in early August 2013, Russian Prime Minister Medvedev said that Georgia should abandon its pursuit of NATO membership and forget about Abkhazia, South Ossetia and the refugee problem. Only then will there be real peace, Medvedev said. Georgia will always be Russia's little brother.

Russian prime minister Medvedev "Georgia will always be Russia's little brother."

Returnees

The only – long-awaited – success that we encountered in 2013 has a sad history. For years, Abkhazia has tried to persuade the refugees from the 19th century – Abkhazians and other Caucasians who fled Russia's armies during the Caucasian War – to return to the motherland. Returnees offer great opportunities for Abkhazia. As a result, it is reaching out to a large diaspora in the former Ottoman Empire, from Turkey to Libya, and across Western Europe and the United States. It would mean access to economic and political networks and renewed loyalty to Abkhazia, which can only be a good thing.

When it comes down to it, the Abkhazians seem less willing to give up their current parochial state.

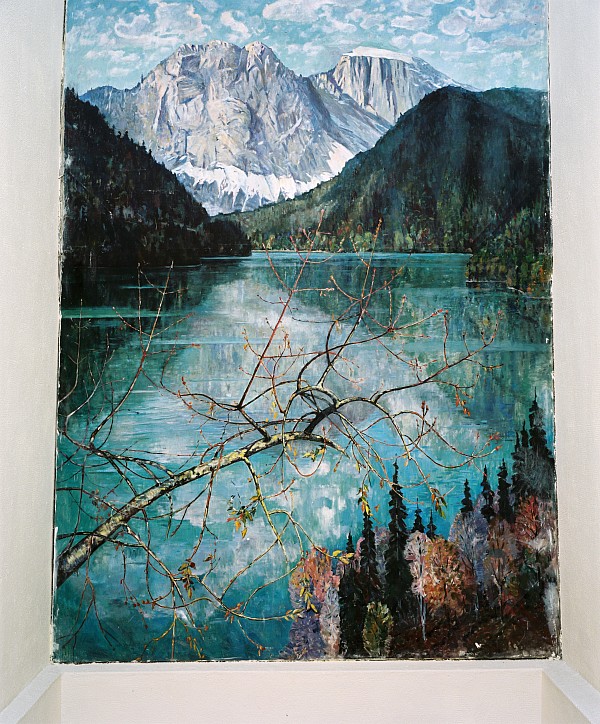

Painting in the hallway of the Ministry of Repatriation, Sukhum, Abkhazia.

Abkhazia has established a ministry dedicated to the repatriation of former compatriots. A handful of Turkish families from Anatolia's arid interior signed up, but only after the war in Syria broke out did the trickle of returnees become a steady stream. Several hundred Syrians moved to Abkhazia in late 2012 and 2013, and were received with a flat, an income and a language course. However, the arrival of predominantly Muslim Abkhazians from the Middle East worries many of the existing inhabitants. Abkhazia is a closed clan society where most people know each other. The country has to throw open its borders if it is to change and modernise but, when it comes down to it, the Abkhazians seem less willing to give up their current parochial state.

Chapter II looks at the background of little-known Abkhazia. Read more about Abkhazia and Georgia in our book Empty Land, Promised Land, Forbidden Land, available online on ISSUU and through our webshop.

Empty land Promised land Forbidden land

Empty land Promised land Forbidden land