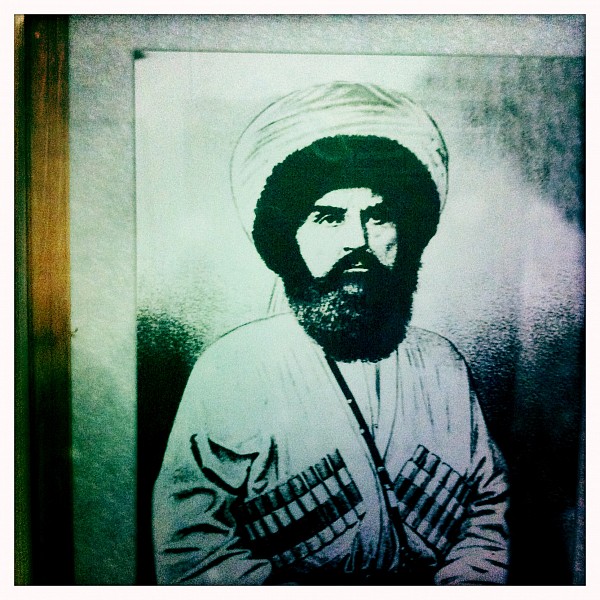

In local museums such as this one in Nalchik, Kabardino-Balkaria, local history has been folklorised & glorified.

The Caucasus will never be peaceful.

In local museums such as this one in Nalchik, Kabardino-Balkaria, local history has been folklorised & glorified.

The Caucasus will never be peaceful.

The Romanticism of the 19th century persisted in 20th-century folklore. The fierce guerrilla fighters of the Caucasian War were translated into tableaux of supernaturally healthy, powerful men, noble warriors, rising above the common hustle and bustle, sitting proudly on horseback; or women – firm, proud types with large bosoms – engrossed in a noble craft such as jewellery making, pottery or fruit preservation. During the Chechen wars in the 1990s, a song did the rounds among the anti-Russian fighters about Baysangur, Shamil’s ally who fought the Russians to the bitter end in the besieged town of Gunib. According to the song, when Shamil signed the peace treaty and surrendered, Baysangur called after him: “Turn around, I will shoot you down!” Shamil did not turn around, knowing that a fighter like Baysangur would never shoot someone in the back. The song was the Chechen answer to the romanticised history written by the Russians.

Shamil’s death in 1859 in the east and the battle of Krasnaya Polyana

Krasnaya Polyana

Sochi region

in 1864 in the west marked the official end of the Caucasian War. But the Caucasus would never be peaceful. Immediately after Shamil's arrest, he was succeeded by an imam in the Dagestani city of Sogratl, who also attracted a fairly large following. All 600 men from the district were exiled to Siberia.

Krasnaya Polyana

Sochi region

in 1864 in the west marked the official end of the Caucasian War. But the Caucasus would never be peaceful. Immediately after Shamil's arrest, he was succeeded by an imam in the Dagestani city of Sogratl, who also attracted a fairly large following. All 600 men from the district were exiled to Siberia.

Many in the North Caucasus regarded the Soviet Union as a good idea, after the poverty, war and terrorism under the tsar.

The North Caucasus under the Soviet Union

After the poverty, war and terrorism under the tsar, many in the North Caucasus regarded the Soviet Union as a good idea. A Soviet-style republic was appealing, for had the North Caucasians not been governed for centuries by the old and wise in their villages and regions instead of tsars and princes? Yet in those first chaotic years of the revolution, the desire for independence also reared its head again. This was intensified by the growing repression, terror and famine of the 1920s and ’30s.

While the remnants of the tsarist wars were still smouldering, the Caucasus cautiously began to rebel against the new regime again. Most of the uprisings did not have national support, but were instigated by smaller gangs, called ‘bandits’ by the Soviets. In the mountains, familiar territory for the Ingush, Chechens, Karachays and Balkars, it was easy to hide and launch guerrilla campaigns. The repercussions became increasingly deadly. According to Soviet troops, the only way to punish the gangs was to cut off their supplies of food and assistance. Entire valleys of villages and hamlets were wiped out in the late ˈ30s and early ˈ40s, with the aim of depriving the guerrilla fighters of their lifelines. Despite this, resistance groups in the mountains continued to fight against the communists until the ’70s.

World War II monument in the village school of Chinar, Dagestan.

World War II monument in the village school of Chinar, Dagestan.

Veterans

The Germans only just reached the Caucasus. At the end of 1942 they ascended Mount Elbrus and proudly planted the Nazi flag at the Elbrus

Elbrus

Kabardino-Balkaria, Russia

. Footage of the event was shown around the world, but it was only the vanguard who would taste this short-lived victory. In the meantime, the war had reached a turning point and the Germans began their unprecedentedly rapid retreat. Less than two and a half years after the Germans had climbed Mount Elbrus, the Russian army had reached the gates of Berlin. But the brief encounter worried the regime in Moscow. In preparation for their advance, the Germans sent spies and propagandists to the Caucasus to pave the way for German 'liberation'. They threw flyers out of aeroplanes that read 'For a free Caucasus'. Under the Germans, the mountain peoples were led to believe, the Caucasus would finally be free.

Elbrus

Kabardino-Balkaria, Russia

. Footage of the event was shown around the world, but it was only the vanguard who would taste this short-lived victory. In the meantime, the war had reached a turning point and the Germans began their unprecedentedly rapid retreat. Less than two and a half years after the Germans had climbed Mount Elbrus, the Russian army had reached the gates of Berlin. But the brief encounter worried the regime in Moscow. In preparation for their advance, the Germans sent spies and propagandists to the Caucasus to pave the way for German 'liberation'. They threw flyers out of aeroplanes that read 'For a free Caucasus'. Under the Germans, the mountain peoples were led to believe, the Caucasus would finally be free.

Under the Germans, the mountain peoples were led to believe, the Caucasus would finally be free.

When war broke out, thousands of Caucasians left for the frontline. Furthermore, the region boasts many veterans, with the Caucasian peoples contributing disproportionately to the war both in terms of soldiers and victims.

Upon returning from the front, many soldiers found a deserted country, where Stalin's paranoid regime had reeked considerable havoc among several peoples.

Deportations

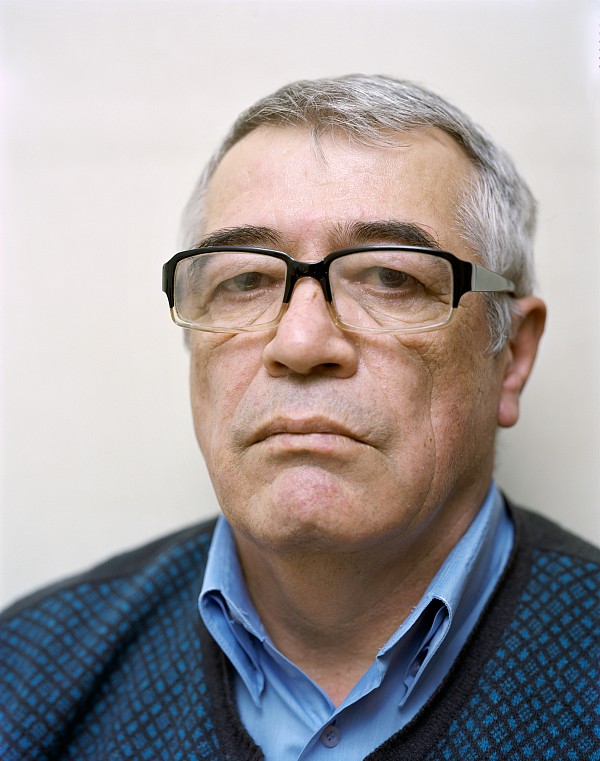

Akhmed Ustarkanov was just 17 when the war broke out. He opens the door of his spacious apartment in Grozny, Chechnya, wearing blue satin pyjamas and a small scull cap. He is tiny. His wife is sent to the kitchen to prepare food and uncork the vodka. He is an old-school Chechen – as Russified as can be – and so we have to drink toasts to life and death, women, guests, friendship and future generations.

Akhmad Ustarkanov

“Stalin called on us to take up arms."

The Caucasus is a region of veterans. No other part of the Soviet Union sent so many men to the front, many will say, after which an argument will ensue over exactly which Caucasian people produced the most soldiers. Roman Eloev (88) was born and raised in Gori, Georgia, where the August War in 2008 got close indeed, he now lives in a converted barn in South Ossetia. The third war in his lifetime was too much for him. He is now a refugee in his own country.

The Caucasus is a region of veterans. No other part of the Soviet Union sent so many men to the front, many will say, after which an argument will ensue over exactly which Caucasian people produced the most soldiers. Roman Eloev (88) was born and raised in Gori, Georgia, where the August War in 2008 got close indeed, he now lives in a converted barn in South Ossetia. The third war in his lifetime was too much for him. He is now a refugee in his own country.

Veteran Akhmed Ustarkanov and his wife in Grozny, Chechnya.

Veteran Akhmed Ustarkanov and his wife in Grozny, Chechnya.

Akhmad Ustarkanov

"It was only on my return home that I was declared a public enemy.”

“It was 3 July 1941,” Ustarkanov remembers. “Stalin called on us to take up arms. I signed up with seven friends from our village, Urus Martan. We were so desperate to fight that we even lied about our age. We were assigned to the cavalry and were given lessons at the barracks in Grozny. But things quickly started to go wrong.” The diminutive 88-year-old man sits on the edge of his seat. “In 1942, the Soviet Union was caught off guard. Stalingrad was under siege and we had to cut our training short to leave for the front. I was deployed as a mounted scout.”

He shows us the evidence of his war: a jacket covered with medals, an endless array commemorating battles, sieges, jubilees and various other tributes. His pride and joy is a photo of him in the Kremlin with Vladimir Putin and Dmitry Medvedev. Ustarkanov left Stalingrad and travelled the country until he was stationed in present-day Kaliningrad to supply the frontline. His war was a long one. After the German troops capitulated, he was immediately sent to the eastern front where the war with Japan still ground on. From there he was sent to Mongolia and then Manchuria. “I was 23 when I was dismissed,” he says. “I came home to an empty Chechnya. I realised later that I’d been lucky. More than 16,000 soldiers from Ingushetia and Chechnya had been captured at the front and sent to camps. It was only on my return home that I was declared a public enemy.”

In 1947, Ustarkanov went to Kazakhstan and found his parents in a small kolkhoz close to the Kazakh mountains. He became a gym teacher at a local school. “It was difficult in Kazakhstan,” he says. “There were a lot of riots between us and the Kazakhs and Russians who already lived there. What we saw as deportation, they saw as an invasion.”

Mamatai Bostanov

“They were the 15 darkest years for our nation.”

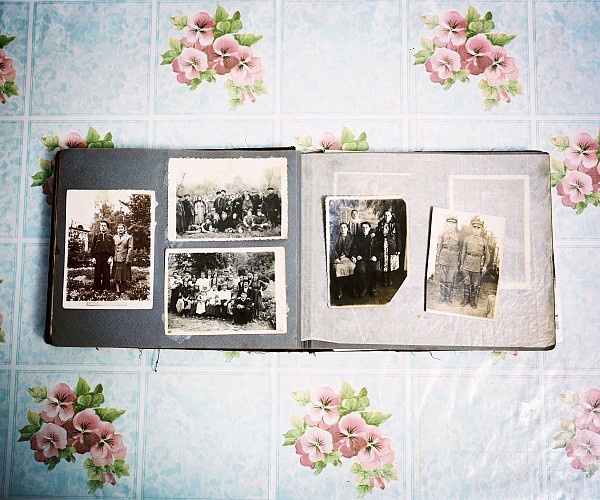

Mamatai with pictures from his days in Kazakhstan.

Mamatai with pictures from his days in Kazakhstan.

“They were the 15 darkest years for our nation,” agrees 74-year-old Mamatay Bostanov in Karachay-Cherkessia

Karachay-Cherkessia

Russia

. It is a clear day and Mount Elbrus towers above the other peaks. The town is a tranquil paradise on the River Kuban, where apple trees hang with fruit and cows and chickens roam the backstreets. Dozens of crates filled with freshly picked apples and pears are stacked in front of Mamatay’s improvised garden bench. “For 14 long days our world was dark and bleak,” he recalls the journey. “Each day we stopped somewhere and were given food. The only thing I can remember is a sort of fish soup. If someone in the carriage had died that day, we gave the body to passers-by. That’s why many of us are buried in places that nobody can remember any more. But even more people died in Central Asia than in the train – of typhoid, malaria, starvation. We died of everything.” His own, small family of five survived the deportation, but his wife lost six of her nine siblings.

Karachay-Cherkessia

Russia

. It is a clear day and Mount Elbrus towers above the other peaks. The town is a tranquil paradise on the River Kuban, where apple trees hang with fruit and cows and chickens roam the backstreets. Dozens of crates filled with freshly picked apples and pears are stacked in front of Mamatay’s improvised garden bench. “For 14 long days our world was dark and bleak,” he recalls the journey. “Each day we stopped somewhere and were given food. The only thing I can remember is a sort of fish soup. If someone in the carriage had died that day, we gave the body to passers-by. That’s why many of us are buried in places that nobody can remember any more. But even more people died in Central Asia than in the train – of typhoid, malaria, starvation. We died of everything.” His own, small family of five survived the deportation, but his wife lost six of her nine siblings.

Mamatai Bostanov

"Typhoid, malaria, starvation. We died of everything."

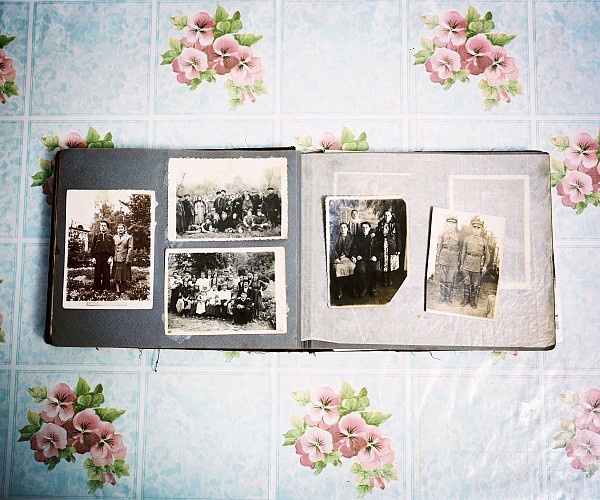

Karachaevsk, Karachay-Cherkessia: the earliest pictures in the photo album of Modalif & Sofia Chomaev are from Kazakhstan.

Karachaevsk, Karachay-Cherkessia: the earliest pictures in the photo album of Modalif & Sofia Chomaev are from Kazakhstan.

She brings out a pile of old photos. “Some of them died there,” she says pointing, “others still live in Central Asia; some are now our neighbours.” It is disconcerting to realise that every family in this village was affected by Stalin’s insane policies. One inhabitant was born in Kazakhstan, another in Kyrgyzstan, while someone else we speak to at a bus stop was a year old when he was deported and 15 when he returned.

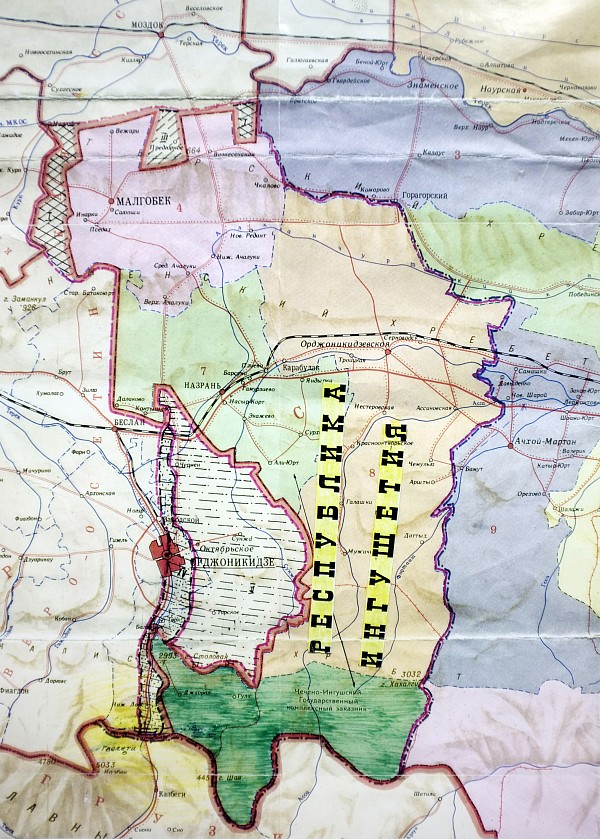

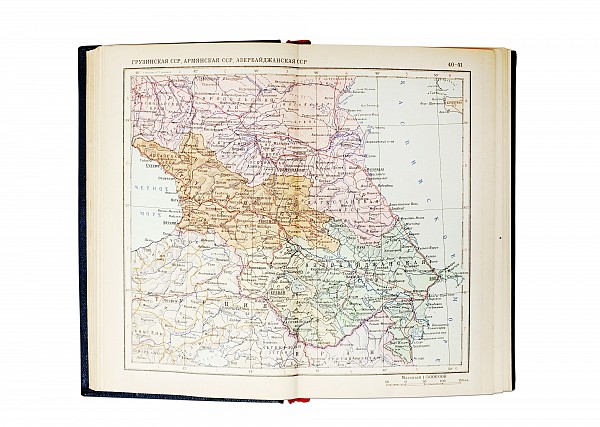

Within a few years the Balkars, Ingush and Chechens had been erased from maps, atlases and reference books.

Few, however, believe that collaboration with the Germans was the real reason for the deportations. “Stalin was Georgian. He wanted to clear this area for Georgians,” says 73-year-old Amir Uzdhanov, also in Karachayevsk. Georgians were living in his home when he came back from Kazakhstan, and in the intervening years his family had been decimated. When his father returned from the war, he found the area deserted. He soon learned that his family and kinsmen were living in Central Asia and followed them there. “He died less than a week after finding us,” says Uzdhanov. “The exhaustion was simply too much for him.”

Monument to the victims of repression and deportation near Nazran, Ingushetia.

Monument to the victims of repression and deportation near Nazran, Ingushetia.

While small resistance groups fought on, the disappearance of almost 500,000 inhabitants from the Caucasus was less like removing the sting from the wasp and more like wiping out the wasp itself. The remaining republics were renamed: Karachay-Cherkessia became the Cherkessian Autonomous Oblast, Kabardino-Balkaria became simply Kabardino. Ingushetia was divided between North Ossetia and the new Russian region of Grozny

Grozny

Chechnya, Russia

. Within a few years the Balkars, Ingush and Chechens had been erased from maps, atlases and reference books.

Grozny

Chechnya, Russia

. Within a few years the Balkars, Ingush and Chechens had been erased from maps, atlases and reference books.

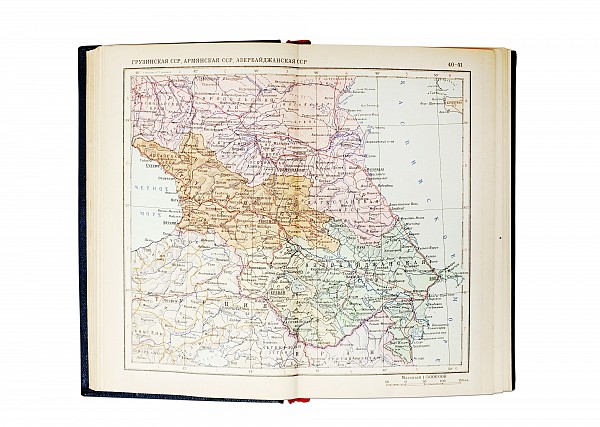

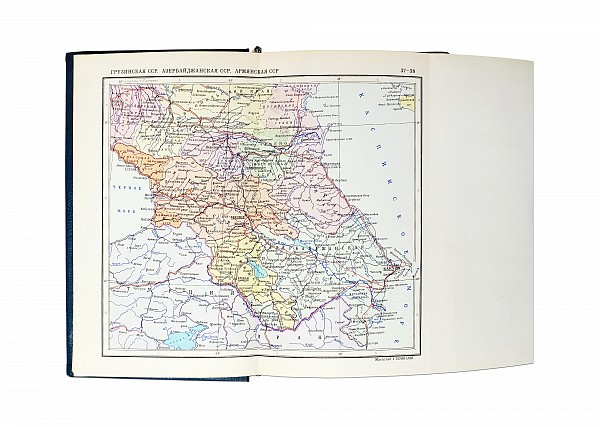

Map from a Russian atlas, 1955 (left). Kabardino-Balkaria is called Kabardin ASSR, the Prigorodny district has been swallowed up by North Ossetia and the Chechen-Ingush ASSR no longer exists.

Map from a Russian atlas, 1955 (left). Kabardino-Balkaria is called Kabardin ASSR, the Prigorodny district has been swallowed up by North Ossetia and the Chechen-Ingush ASSR no longer exists.

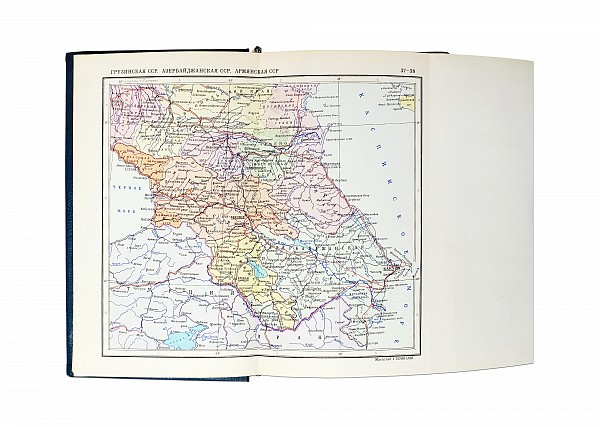

In the next edition from 1966 (right), Kabardino-Balkaria’s old name has been reinstated and the Chechen-Ingush ASSR has reappeared. Only the Prigorodny district has remained Ossetian.

In the next edition from 1966 (right), Kabardino-Balkaria’s old name has been reinstated and the Chechen-Ingush ASSR has reappeared. Only the Prigorodny district has remained Ossetian.

Around 20 per cent of the deportees died during the journey or shortly after their arrival in Central Asia.

Once again the mountain peoples were decimated.

Once again, following the Caucasian War, the civil war around 1920 and The Great Terror of the 1930s, the mountain peoples were decimated. The deportees were subjected to severe restrictions. They were not allowed to leave the villages to which they had been relocated without permission from the police. In the chaos of the journey, some families were separated for years. Anyone caught breaking the rules was brutally arrested and sent to prison camps in Siberia. An NKVD document in the deportation monument shows that of the around 24,000 people who arrived in South Kazakhstan in the spring, 357 were arrested and 1,267 had died by 15 June 1944.

Mamatai Bostanov

"Then we received the news that we were allowed to return home...”

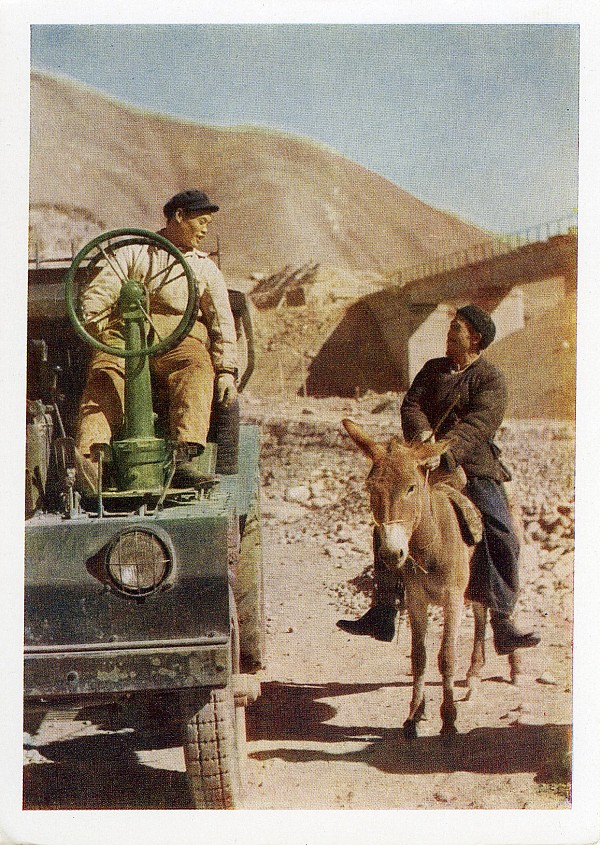

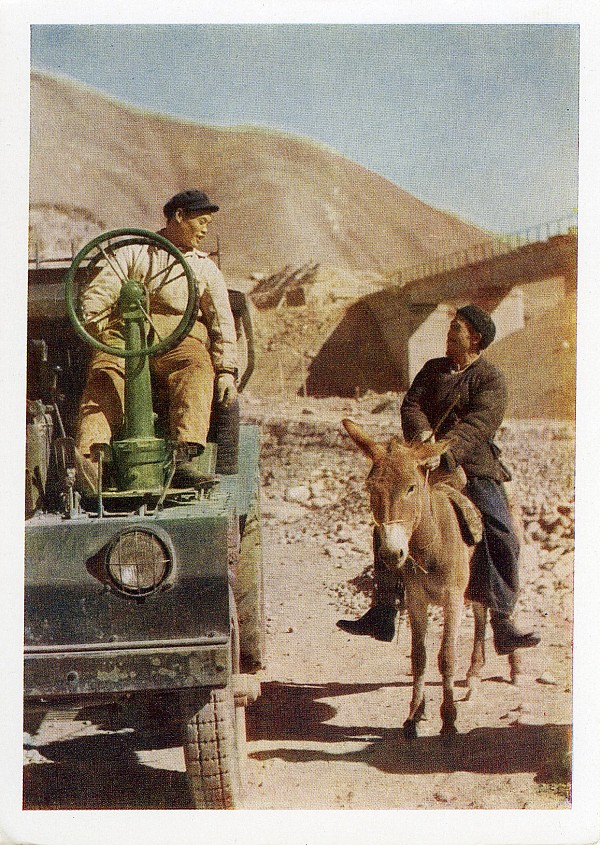

Construction of the railway close to Alma-Ata (Kazakhstan) (1959)

Construction of the railway close to Alma-Ata (Kazakhstan) (1959)

Survival in these fragmented communities thus became a matter of creativity. One of the solutions was to take multiple wives – a measure sanctioned by the Koran to compensate for the shortage of men in times of war and repression. The women married young and the Chechens, Ingush and Balkars sought each other out where possible.

“Once we were in Central Asia, nobody seemed to care about our fate,” says Mamatay Bostanov, from Karachayevsk. “We wrote endless letters to the Central Committee of the Communist Party, but nothing happened.” The Karachay felt betrayed, but then Stalin died. The shock reverberated through the Soviet Union. It is impossible for outsiders to understand the Orwellian worship of a person who caused so much suffering. For Mamatay and his family, it seemed like the end of the world. “We cried our eyes out,” he says. “We always sang songs in which he was the father figure. He meant everything to us and suddenly he was gone. We had no idea how we or the Soviet Union could go on. Then we received the news that we were allowed to return home...”

Nikita Khrushchev

"If Stalin could have found enough space somewhere to deport Ukrainians, he would certainly have done so."

Under the new leader, Nikita Khrushchev, Stalin's reign of terror was partly reversed. In his historic 'secret' speech of 25 February 1956, Khrushchev said that the deportations were not dictated by any military considerations. “Thus, at the end of 1943, when there already had been a permanent change of fortune at the front in favour of the Soviet Union, a decision concerning the deportation of all the Karachays from the lands on which they lived was taken and executed.” Khrushchev recited the names of all the other nations and ended the list with the cynical observation that if Stalin could have found enough space somewhere to deport Ukrainians, he would certainly have done so.

Moscow was terrified that the hundreds of thousands of deportees would clash with the Georgians, Russians and Ossetians now living in their houses. To prevent this, Moscow offered the Ingush the steppes of South Russia. The Chechens could also be located further north, beyond the River Terek and in North Dagestan.

Monument to those who rebuilt the village after returning from exile. Uchkeken, Karachay-Cherkessia.

Monument to those who rebuilt the village after returning from exile. Uchkeken, Karachay-Cherkessia.

No such solution was proposed for the Karachays and Balkars, who were to be reintegrated into their home countries. As soon as Khrushchev gave the go-ahead in 1956, however, the floodgates opened. The majority of people moved back as soon as they could, to the homelands they had been forced to leave ten years earlier.

From 1944, the Russians, Georgians, Cossacks, Ossetians and others cultivated the fields and inhabited the abandoned houses where the deportees had once lived. To a large extent they were also part of the complicated political manoeuvres aimed at keeping the Caucasus peaceful and loyal. To this end, tens of thousands of South Ossetians from Georgia were brought to the North Caucasus, primarily to repopulate the Prigorodny district. And now the mountain peoples, whom the Russians had so feared for 150 years that they had erased them from the history books, had come back – and had received reparation and compensation to boot. Stories circulated throughout the North Caucasus about the dreaded returnees who entered homes at night to claim their former property. It led to a spontaneous exodus of new settlers from the North Caucasus. It must have been an incredibly confusing time for everyone.

One out of many checkpoints along the M29, between Makhachkala and Khazavyurt (Dagestan).

The North Caucasus

General map

? In the run-up to the Olympics, Moscow has tried to defuse tensions by investing billions in the region. There are plans to build a large ski resort in every republic, in a bid to boost tourism and the economy. Alexander Khloponin, a special deputy prime minister and Putin confidant, has been appointed to achieve this.

The internal border between North Ossetia and Ingushetia. The road behind it leads to the new ski resorts, hotels and renovated sanatorium. Closed territory for foreigners.

Critical journalists are few and fear for their lives.

Caspian Sea

Russia

. They are all dots on a map compared to the enormous land mass of mother Russia that stretches out to the north.